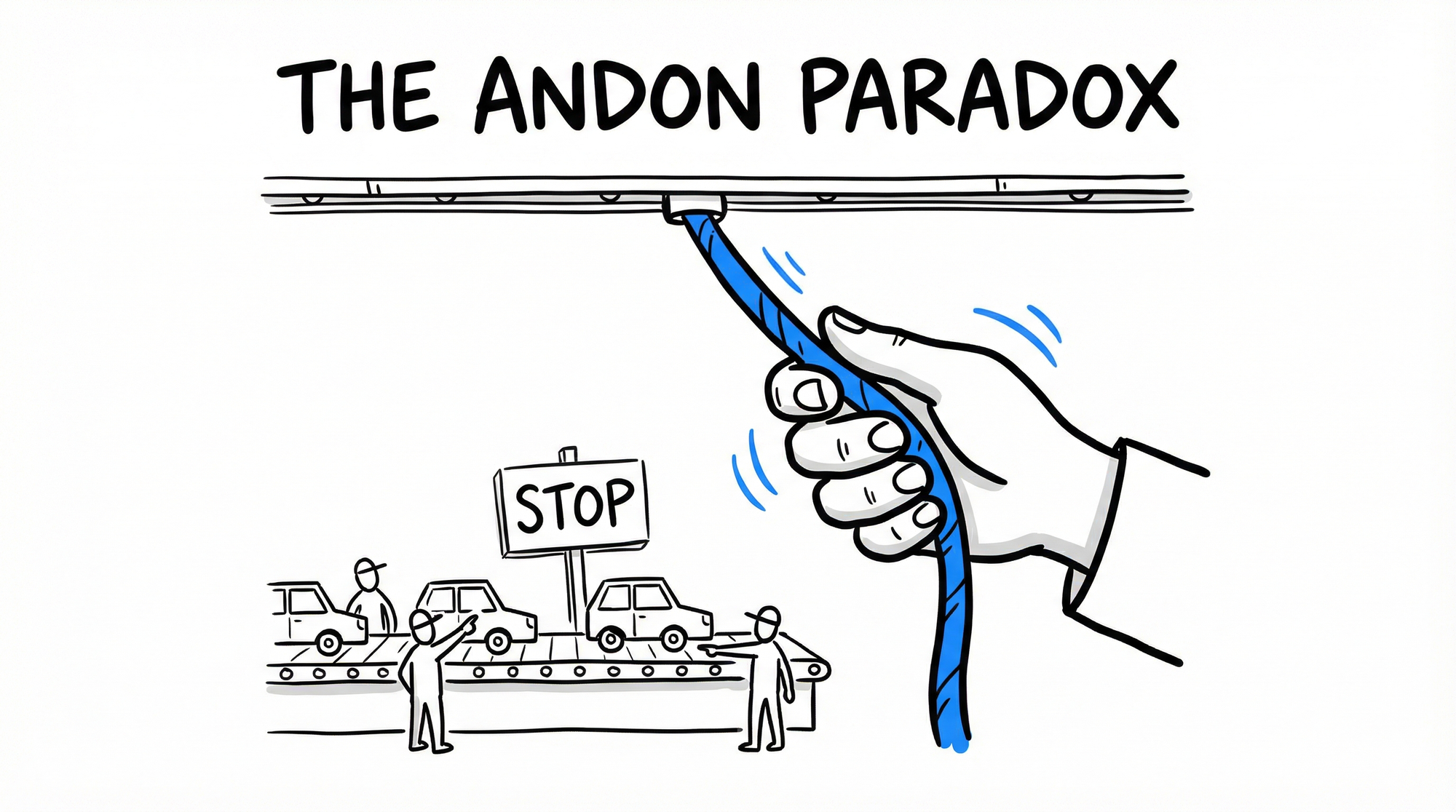

The Andon Paradox

The tool is never the constraint. The permission to use it is.

In 1984, Toyota took over a General Motors factory in Fremont, California.

The plant had been GM's worst. Absenteeism ran at 45%. Cars came off the line so broken they had to be towed to repair bays. Management and the United Auto Workers were in constant conflict. The workers were considered unemployable.

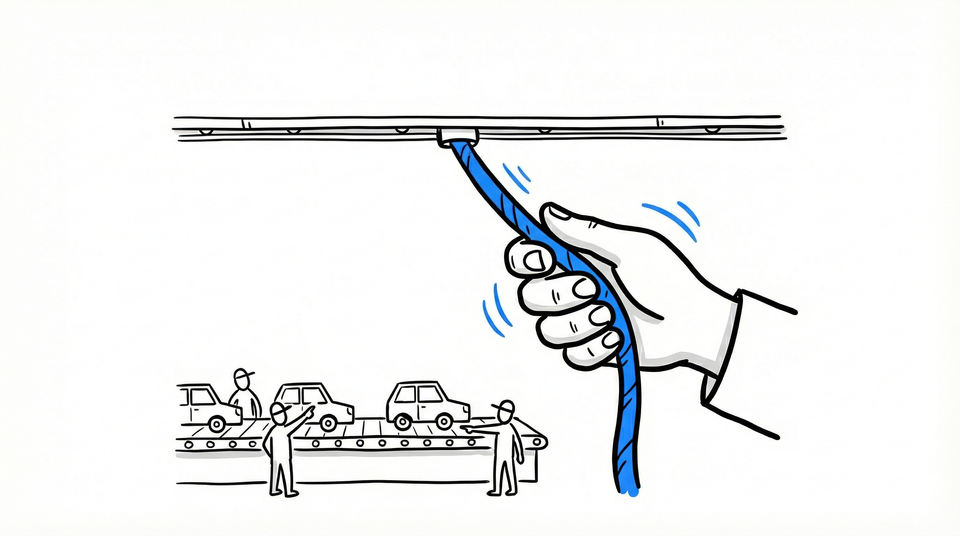

Toyota didn't replace them. They installed a cord.

Within two years, those same workers were producing cars with defect rates matching Toyota's Japanese factories. Absenteeism dropped to 3%. It became GM's most productive plant.

The cord was called Andon.

A thin nylon rope hanging on hooks along the assembly line. Any worker could pull it to stop production.

The idea traced back to Sakichi Toyoda's automatic loom, invented in 1924. When a needle broke, the loom stopped automatically. No defective fabric flowed downstream. Taiichi Ohno, architect of the Toyota Production System, extended this principle to assembly lines in the 1960s. If a worker spotted a problem, they could stop everything.

Pull the cord. A team leader arrives within seconds. If the problem can't be fixed quickly, the entire line stops. A cheerful song plays. Everyone knows there's a problem. Everyone helps solve it.

Short-term, this destroyed productivity. Lines stopping constantly. Output plummeting.

Toyota kept going.

Within seven years, their process was nearly flawless. They were producing the best cars in the world. Every cord pull made the system better. Problems surfaced when context was fresh. Fixes happened before defects cascaded. The feedback loop collapsed from weeks to seconds.

When American car companies heard about the Andon cord, they copied it.

They installed the cord. They gave workers authority to pull it.

Nobody pulled it.

Not because there were no defects. There were plenty. Workers saw problems every day.

They didn't pull because they were afraid.

In traditional American factories, stopping the line meant you were the problem. You slowed production. You cost the company money. You got yelled at. Maybe fired. The culture said: keep your head down, keep the line moving, let someone else deal with it downstream.

The tool was identical. The culture was opposite. The results followed.

The tool is never the constraint. The permission to use it is.

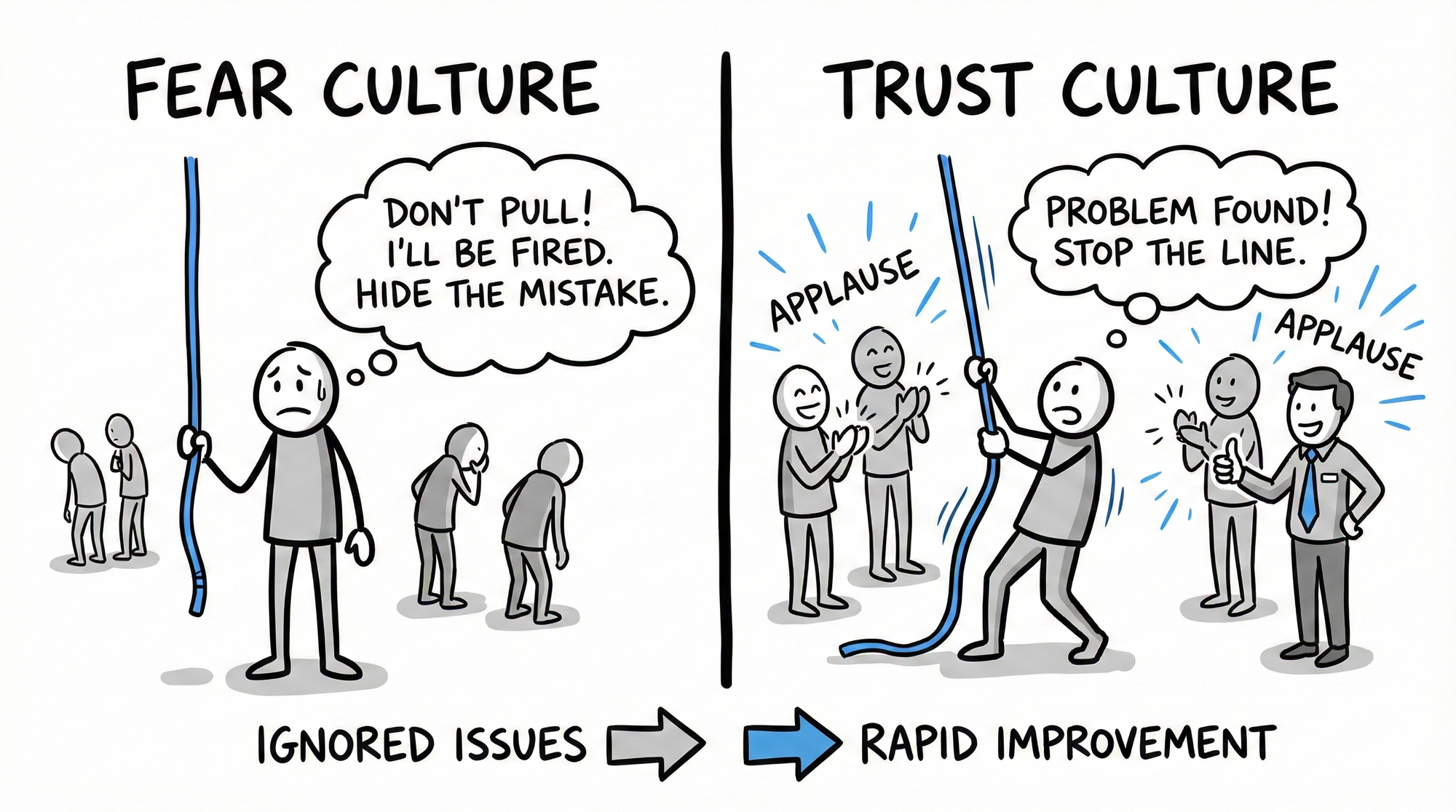

At the Fremont plant (called NUMMI, for New United Motor Manufacturing), Toyota didn't just install tools. They rebuilt trust through specific actions.

When Tetsuro Toyoda visited and encouraged a worker to pull the cord, by noon the entire factory had heard about it. The next day, workers pulled it over ten times. Within a month, they averaged 100 pulls per day.

The message spread through demonstration, not declaration.

Mike Hoseus, who worked at NUMMI and later wrote about Toyota culture, describes being applauded for pulling the cord and admitting a mistake. Not tolerated. Not accepted. Applauded.

Toyota's policy was explicit: no criticism for pulling the cord. Even false positives never triggered blame. Management promised workers they could stop the line. Then management kept that promise. Day after day. Worker after worker. Until workers believed it.

Trust isn't announced. It's accumulated.

The Andon principle appears wherever feedback matters.

Amazon calls their version the "Customer Service Andon Cord." Jeff Bezos described it in his 2012 shareholder letter: automated systems detect when customer experience falls below standards and proactively respond. The human is authorized to stop the process.

In software, elite performers deploy hundreds of times per day. Each deployment is a feedback loop. Something wrong? Roll back immediately. Context fresh. Fix cheap. Low performers deploy monthly. Problems discovered weeks later. Context gone. Fix expensive.

The pattern is consistent: speed of feedback determines speed of learning. But feedback only works if people feel safe providing it.

GM and Toyota dissolved the NUMMI partnership in 2010. GM had spent decades trying to replicate the transformation in other plants. They copied the tools. They couldn't copy the trust.

The Fremont factory sat empty. Then a South African entrepreneur bought it to build electric cars.

Today, the former NUMMI plant is Tesla's main factory.

The building that taught America how feedback loops work is still teaching.

If you're trying to collapse feedback loops in your organization, the Andon Paradox offers a diagnostic.

Do people use the tools you've given them?

If you have error reporting but nobody reports errors, that's not a tool problem. If you have retrospectives but nobody raises real concerns, that's not a process problem. If you have an open-door policy but nobody walks through, that's not an access problem.

It's a permission problem.

The fix isn't better tools. It's what happens when someone uses them.

What happens in your organization when someone surfaces a problem?

If they get blamed, they'll stop. If they get thanked, they'll continue. If they get applauded, you might be Toyota.

This post explores Temporal Information Degradation, one of four dynamics from The Momentum Engine. When feedback loops are slow, organizations fly blind. The Andon cord is an architectural solution. But architecture without culture is just decoration.