The Dunbar Trap

There's a number written into your brain. It determines how many people you can actually work with.

There's a number written into your brain.

It determines how many people you can actually work with. Most organizations ignore it.

The number is 150.

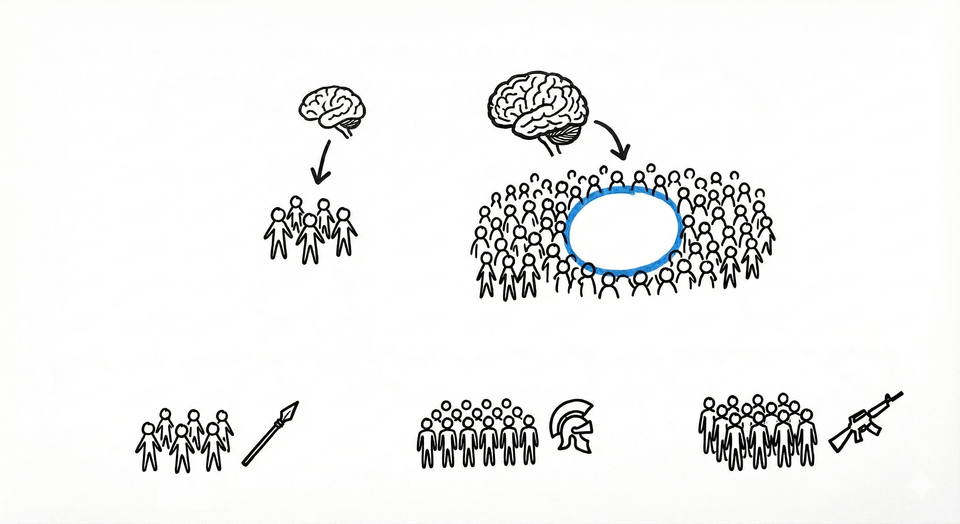

In 1992, a British anthropologist named Robin Dunbar was studying primates.

He noticed something strange: across species, there was a consistent relationship between neocortex size and social group size. Bigger neocortex, bigger groups. The correlation was tight.

Dunbar extrapolated to humans. Based on our neocortex, he predicted that humans should max out at about 148 stable social relationships. He rounded to 150.

The scientific community was skeptical. Then researchers started looking for evidence.

Hunter-gatherer societies averaged 148.4 individuals. Neolithic villages from 6000 BC clustered around 150. Roman legions organized around centuries of roughly 100 men. Modern military companies worldwide average 130-150 soldiers.

The number kept appearing. Not because anyone planned it. Because 150 is where human cognitive capacity hits a ceiling.

The Hutterites figured this out 400 years ago.

These Christian communities, similar to the Amish, have strict rules about community size. When a colony approaches 150 members, they split it in two.

Not 200. Not 100. One hundred fifty.

When asked why: "At 150, you can manage by peer pressure. Everyone knows everyone. Above 150, you need rules. You need hierarchy. You need police."

Robin Dunbar, studying the Hutterites decades later, found their pattern precise. They typically wait until the colony reaches about 200, then split into groups of 150 and 50. Not two groups of 100. The Hutterites intuited that 150 is more stable than 100, and 50 is a natural sub-group.

Four centuries of data. The pattern holds.

Bill Gore discovered the same number through trial and error.

In 1958, Gore and his wife Vieve started a company in their basement. It grew. They moved to a factory. The factory grew.

Then one day, Gore walked through his plant and realized he didn't recognize everyone.

He started counting. Around 150 employees, things got "clumsy." His word. Informal communication broke down. The sense of community evaporated.

So Gore made a rule: no factory would exceed 150 employees.

"We decided" became "they decided" past 150, as management writer Gary Hamel explained. Below 150, workers felt ownership. Above 150, they felt like employees.

Today, W.L. Gore has 9,500 associates and generates $3.5 billion annually. They scaled by staying small. Ten plants in Flagstaff alone. But none exceeds 200 people.

The military learned this centuries earlier.

In 1631, King Gustav II Adolph reorganized the Swedish Army. He needed units large enough to be effective but small enough for cohesion. He chose 150 men per company.

It wasn't arbitrary. Combat requires trust. Trust requires relationships. Relationships require cognitive capacity. At some point, a unit becomes too large for soldiers to know each other well enough to fight together.

The 150-man company became standard across modern armies. Not because generals copied each other. Because the constraint is biological.

The math explains why.

In a group of 5, there are 10 possible relationships to maintain. In a group of 15, there are 105. In a group of 50, there are 1,225. In a group of 150, there are 11,175.

Coordination cost grows with the square of group size. Capacity grows linearly. At some point, coordination overwhelms capacity.

This is why startups beat giants. A 3-person startup has 3 relationships to manage. A 300-person company has 44,850. The startup isn't smarter. They have less friction.

But 150 isn't the only number.

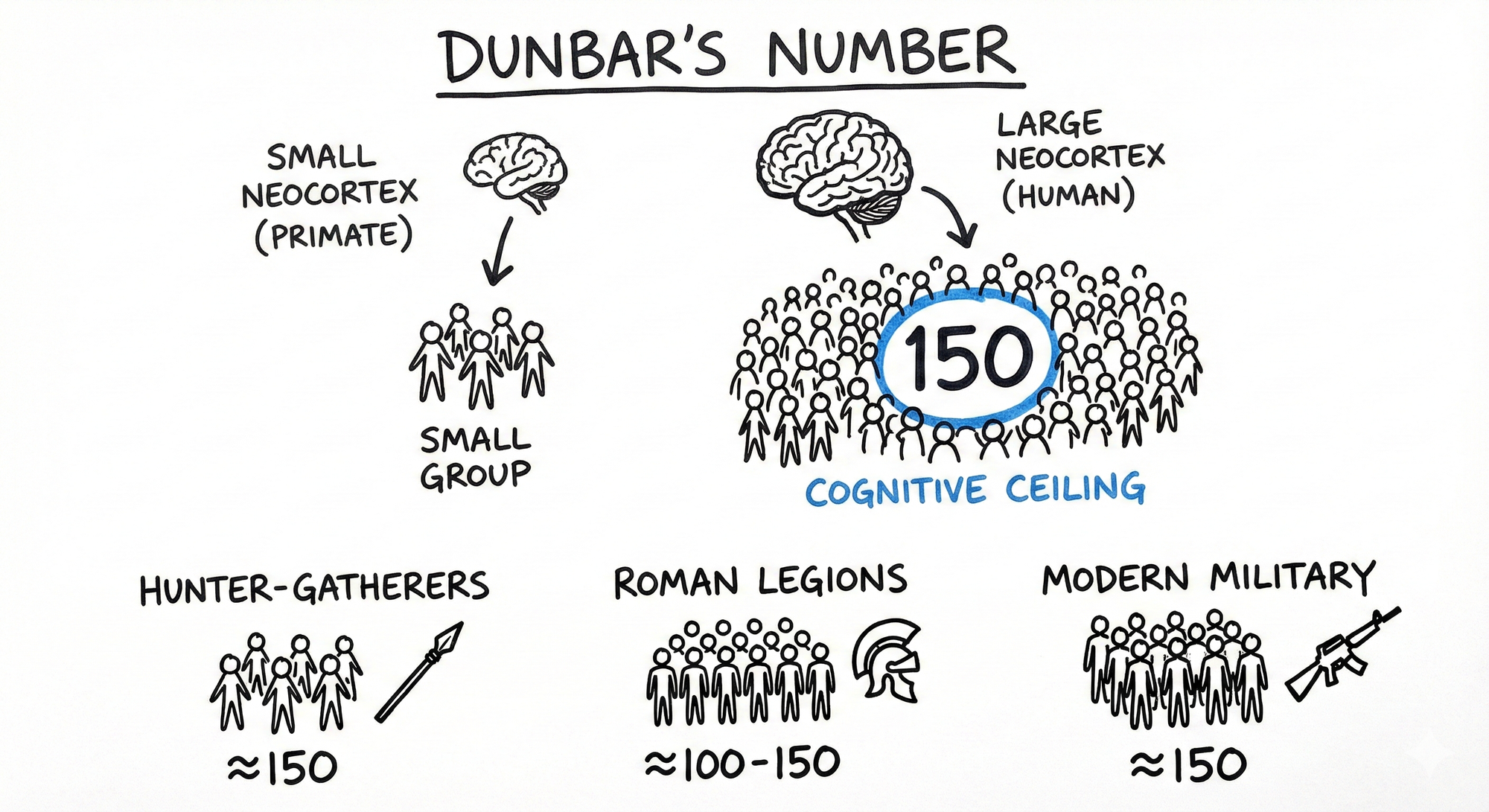

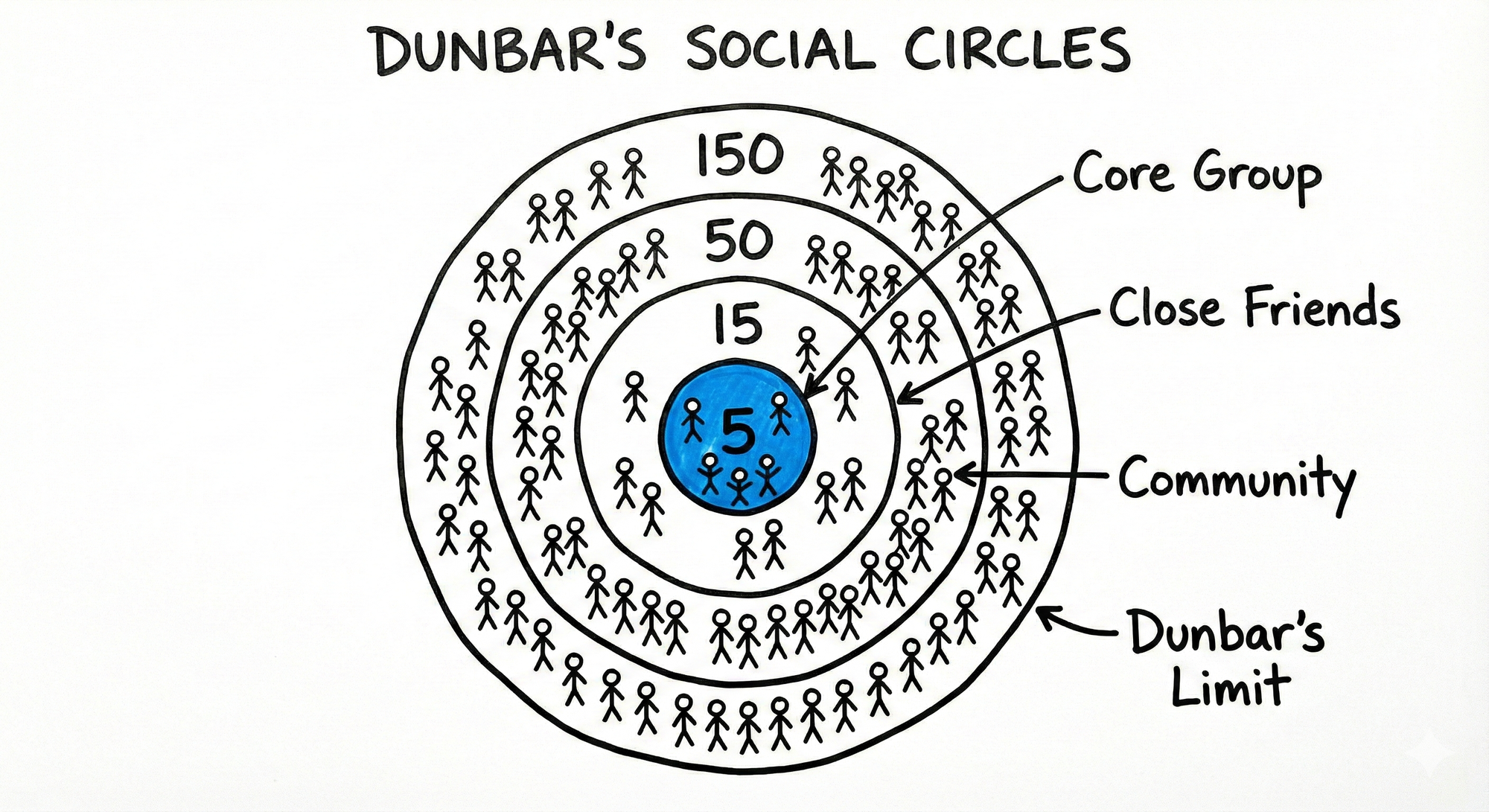

Dunbar's research identified a nested hierarchy:

- 5: Your core support group. People you'd call in a crisis.

- 15: Close friends you see regularly.

- 50: People you'd invite to a large gathering.

- 150: People you can maintain stable relationships with.

Each layer expands by roughly a factor of three. Each layer has different relationship quality.

Your 5-person executive team makes decisions through conversation. Your 15-person leadership team needs structured meetings. Your 50-person department needs processes. Your 150-person organization needs hierarchy.

The constraint isn't "big is bad." Different sizes require different coordination architectures. The mistake is treating a 150-person organization like a 15-person one. Or expecting a 50-person department to coordinate like a 5-person team.

The diagnostic is simple.

When "we" becomes "they," you've crossed a threshold.

When informal communication stops working, you've crossed a threshold.

When people need org charts to know who does what, you've crossed a threshold.

The fix isn't fighting biology. It's designing around it.

Keep teams small. Five to seven people.

Keep organizational units near 150. That's where peer accountability works.

When you grow past these thresholds, change your coordination architecture. Add structure. Add explicit interfaces. Stop pretending you can coordinate informally when you can't.

The Dunbar number isn't a suggestion. It's a biological constraint.

Design accordingly.

This post explores Coordination Cost Scaling, one of four dynamics from The Momentum Engine. Your brain has limits. So does your organization. The question is whether you're designing within those limits or pretending they don't exist.