The Flip Principles

How to find the counterintuitive lever hiding in plain sight.

You've always suspected the logical answer isn't the best answer.

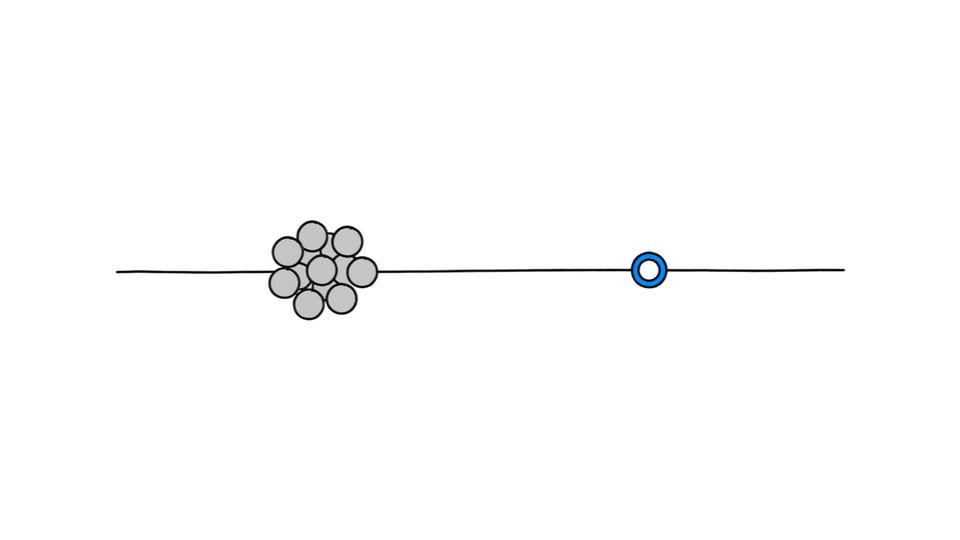

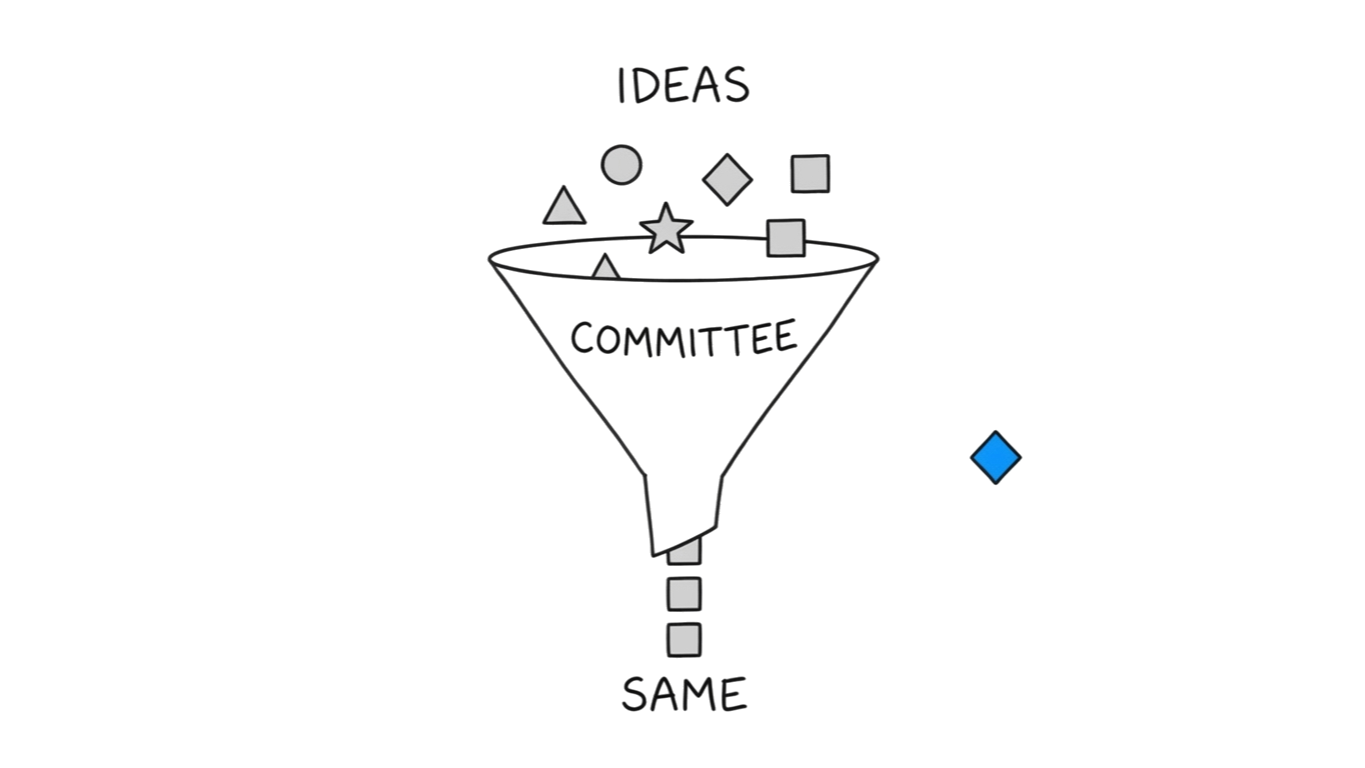

Every competitor runs the same analysis, reads the same research, draws the same conclusions. And arrives at the same position.

Logic produces sameness. But that's not why it dominates.

Logic dominates because it's safe. Nobody gets fired for the reasonable choice. The spreadsheet-backed choice. The choice that every other company in the category also made.

The counterintuitive choice? That one has your name on it. If it fails, you're the person who suggested the skull on the water bottle. The person who told Hertz customers you're second-best. The person who aired a Super Bowl ad that doesn't mention the product.

The flip isn't an intellectual problem. It's a courage problem. The companies that break through aren't smarter. They have someone willing to be wrong in public. Someone who'll sit in a room where every face says this is insane and say: run it.

Four stories. Four flips. One pattern.

Own What Nobody Wants

In 1963, Avis had been losing money for 13 years straight. Hertz owned 61% of the car rental market. Avis had 29%.

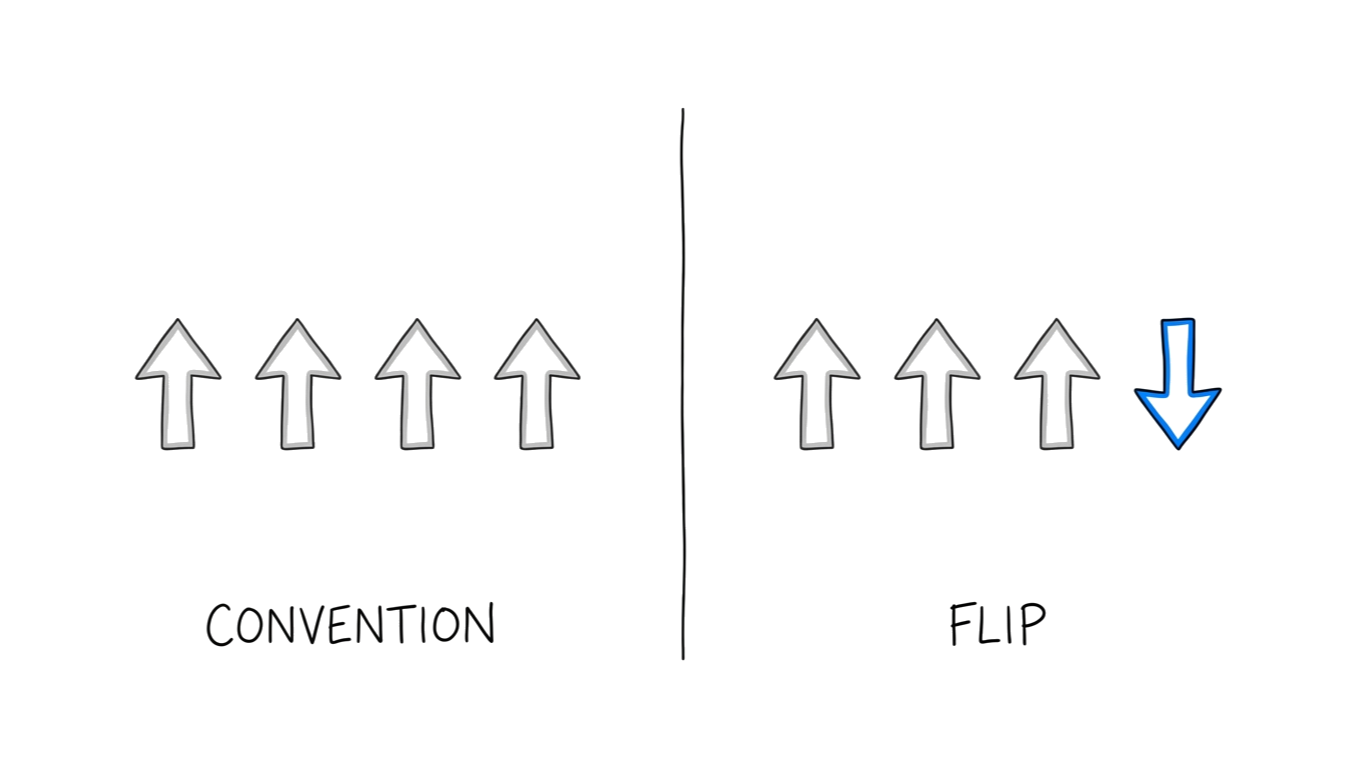

Every instinct in advertising says: claim superiority. Lead with strengths. Never acknowledge a competitor by name.

DDB's Paula Green wrote six words that broke every rule: "We're #2. We Try Harder."

The agency's own staff objected. Green had researchers survey airport travelers. Half interpreted "Number Two" negatively. Bill Bernbach looked at the data and asked: "What about the other 50%?"

They ran it.

Within a year, Avis went from a $3.2 million loss to a $1.2 million profit. Their first profitable year in over a decade. By 1966, market share climbed from 29% to 36%.

David Ogilvy called it "diabolical positioning."

Avis didn't hide the weakness. They made the weakness the argument. Second place means we have to work harder.

The vulnerability was the proof.

Strip the Label

On May 24, 1976, Steven Spurrier organized a blind wine tasting in Paris.

Nine French judges. The most respected palates in France. The co-director of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. The head sommelier of La Tour d'Argent. The editor of La Revue du Vin de France.

They tasted ten wines. Five French, five Californian. Without knowing which was which.

The Californians won both categories. Chateau Montelena took the white. Stag's Leap Wine Cellars took the red.

Judge Odette Kahn demanded her scorecard back. Spurrier refused.

George Taber, the only journalist present, filed a four-paragraph story for Time magazine. It became the most significant news story ever written about wine.

The wine didn't change. The label disappeared.

Same liquid, different frame. The Judgment of Paris didn't prove California wine was superior. It proved that the belief "French wine is superior" was doing most of the work.

What you remove can matter more than what you add.

Change the Environment, Not the Message

In the early 1990s, Jos van Bedaf managed the cleaning department at Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport.

He had a problem. Men's restroom floors were consistently messy.

Van Bedaf remembered something from his military service decades earlier. Someone had drawn a small dot inside a latrine. That latrine stayed cleaner than the others.

He proposed etching a small housefly into each urinal. Just above and slightly left of the drain.

Spillage dropped by an estimated 80%. Total restroom cleaning costs fell roughly 8%.

No signs. No instructions. No lectures about courtesy.

One image, smaller than a thumbnail, changed more behavior than any posted rule ever had. The entire intervention cost almost nothing. A ceramic mold modification.

When Richard Thaler won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2017, journalists led with the Schiphol fly. It became the defining example of nudge theory.

The smallest change in the environment outperformed the loudest change in the message.

The Ad Nobody Could Approve

Apple's board hated the ad.

Ridley Scott had directed it. Lee Clow and Steve Hayden at Chiat/Day had created it.

Sixty seconds. Grey drones march in lockstep. A woman in red sprints down the aisle and hurls a sledgehammer through a giant screen. Fade to black. "On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won't be like '1984.'"

The board wanted to sell the Super Bowl airtime back. John Sculley got cold feet. Mike Markkula suggested firing the agency.

Jay Chiat sold back the 30-second slot. Then he deliberately failed to sell the 60-second one.

The ad ran during Super Bowl XVIII on January 22, 1984. It aired once nationally. Never again as a paid spot.

Apple sold 72,000 Macintoshes in the first 100 days, exceeding projections. But the real impact wasn't in units. It was in the category it created: Apple as the company for people who think differently.

If you had run "1984" through a standard strategy review, someone would have killed it. "This doesn't explain the product." "Customers want to know the specs." "This will confuse people."

All true. All irrelevant.

The irrationality was the feature. Competitors couldn't copy what they couldn't explain to a committee.

That's the real moat. Not the idea itself. The willingness to run it. If every decision-maker in the room can approve it, every competitor in the market can replicate it.

The Pattern Beneath

Four flips. Four industries. One mechanism.

Avis owned what nobody wanted. Spurrier stripped the label. Van Bedaf changed the environment instead of the message. Chiat/Day made something no committee would approve.

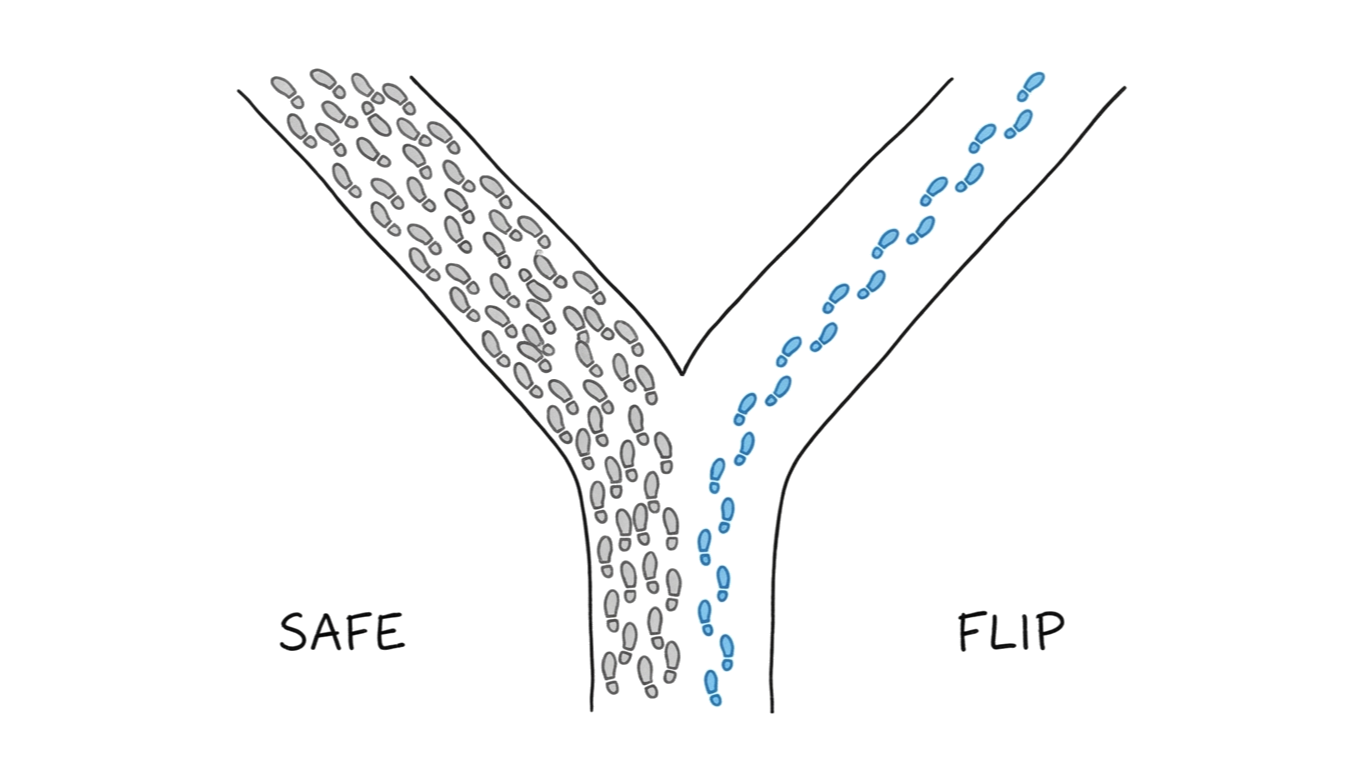

Each followed the same structure: find the position that logic rules out, test whether it creates distinctiveness instead of confusion, and commit before the committee kills it.

The flip can also fail. In 1985, Coca-Cola changed its formula to win the Pepsi Challenge blind taste tests. New Coke won the sip. But people weren't buying the sip. They were buying the label. Coca-Cola flipped the product when the perception was the asset. Sixty-seven thousand angry calls later, they reversed course.

The logical answer is available to everyone. That's precisely why it doesn't work. And the reason it's available to everyone is the same reason everyone picks it: it's the safe choice. The choice nobody gets fired for.

The flip isn't hidden. It's avoided.

The flip tells you what perception shift you're creating. But a perception shift that lives in a strategy deck doesn't shift anything.

The Vehicle System breaks down Hook, Hold, Close and the architecture that turns a clever insight into something unforgettable.

This is the second cylinder of The Perception Engine.