The Vehicle System

Why the right message in the wrong sequence kills campaigns.

You've watched campaigns that should have worked.

The creative was sharp. The product was real. The message was clear. And somehow, nothing moved.

You suspected the problem wasn't what they said. It was when they said it.

You were right.

On March 6, 2012, a man stood in a warehouse in Gardena, California. Behind him: a $4,500 camera, a conveyor belt, and a bear suit he'd rented for the day.

Michael Dubin pressed record.

Ninety seconds later, Dollar Shave Club had a video. No mention of blade count. No close-up of the product. No price comparison chart. Just a guy walking through a warehouse, making you laugh. Making you wonder what this company actually sold.

The video hit YouTube that morning. By Friday, 4.75 million people had watched it. In the first 48 hours, 12,000 people had ordered razors they'd never held from a company they'd never heard of.

Four years later, Unilever paid roughly $1 billion for the brand that video built.

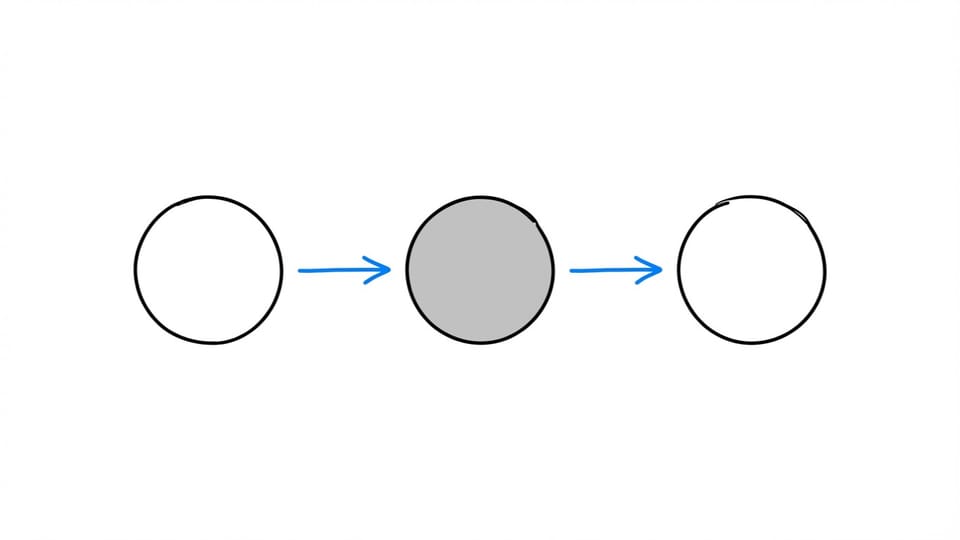

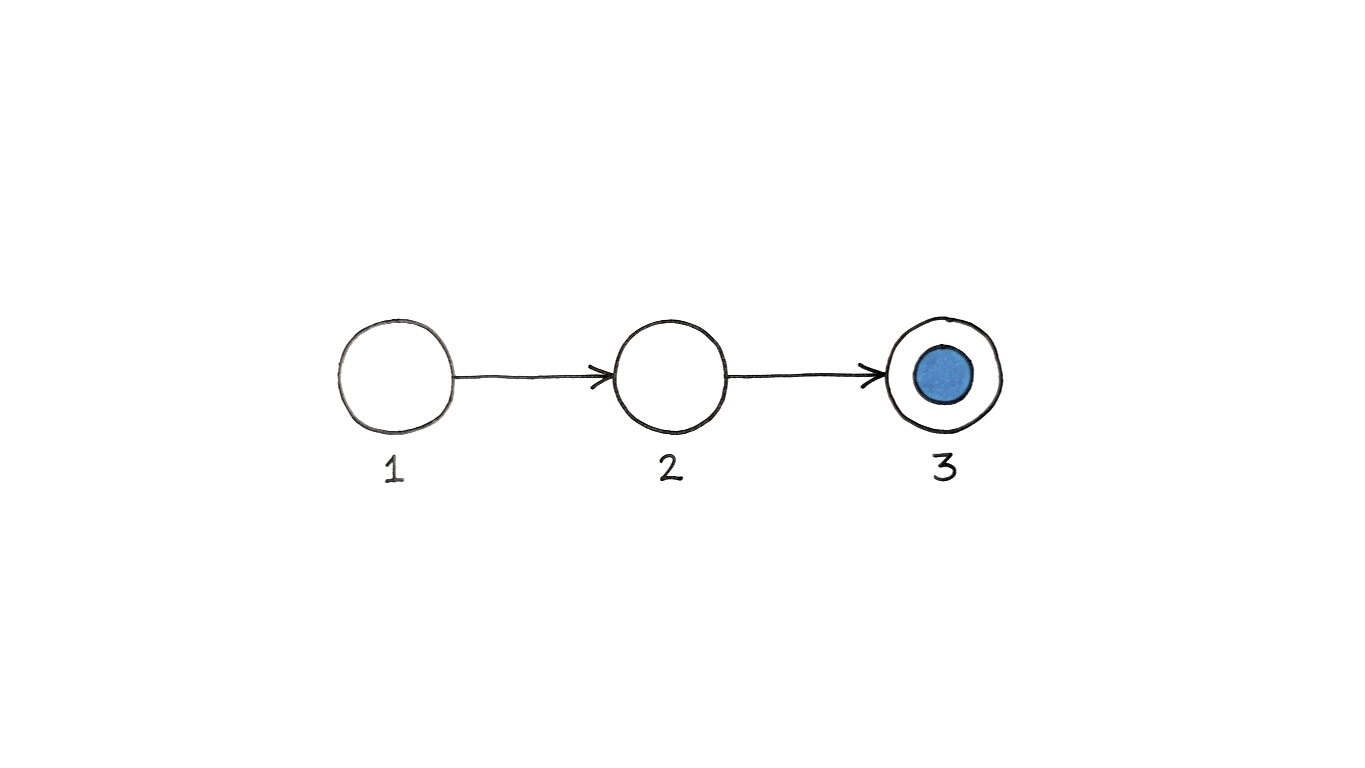

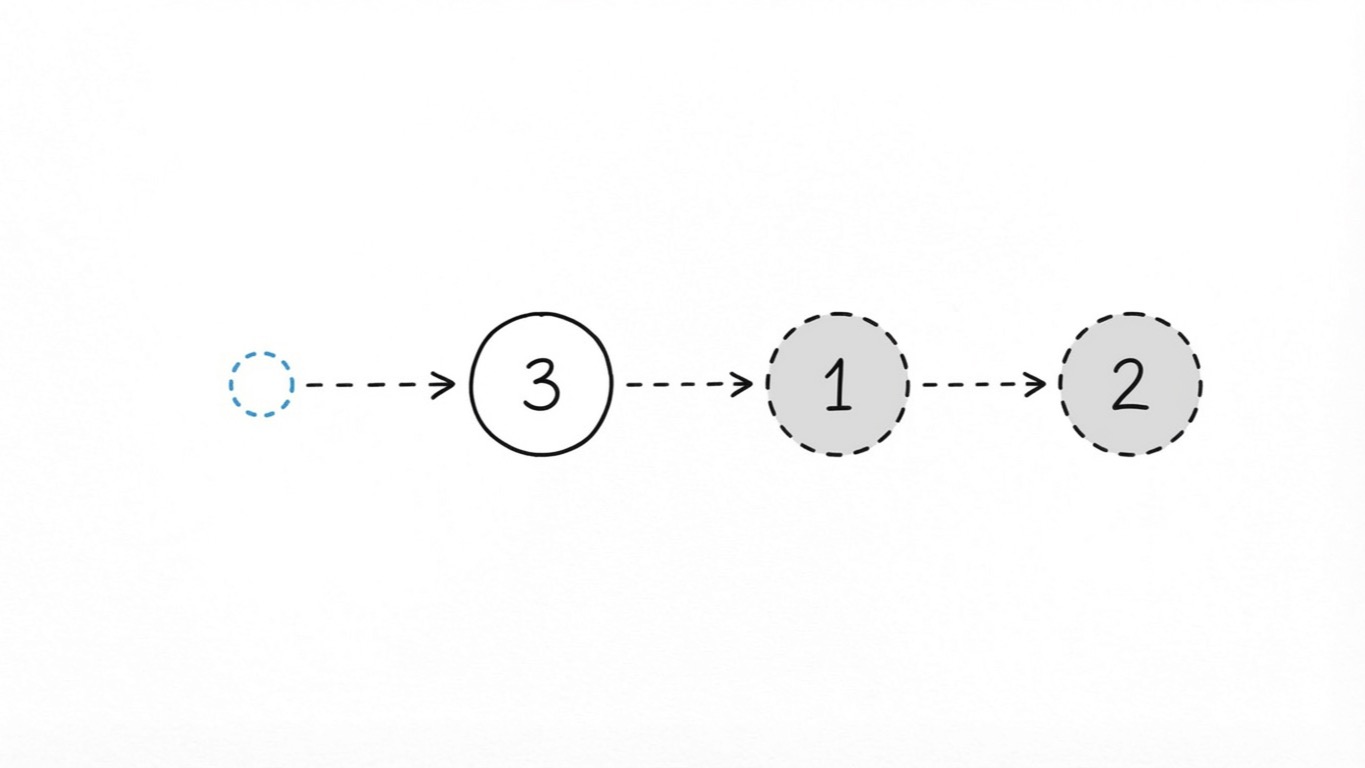

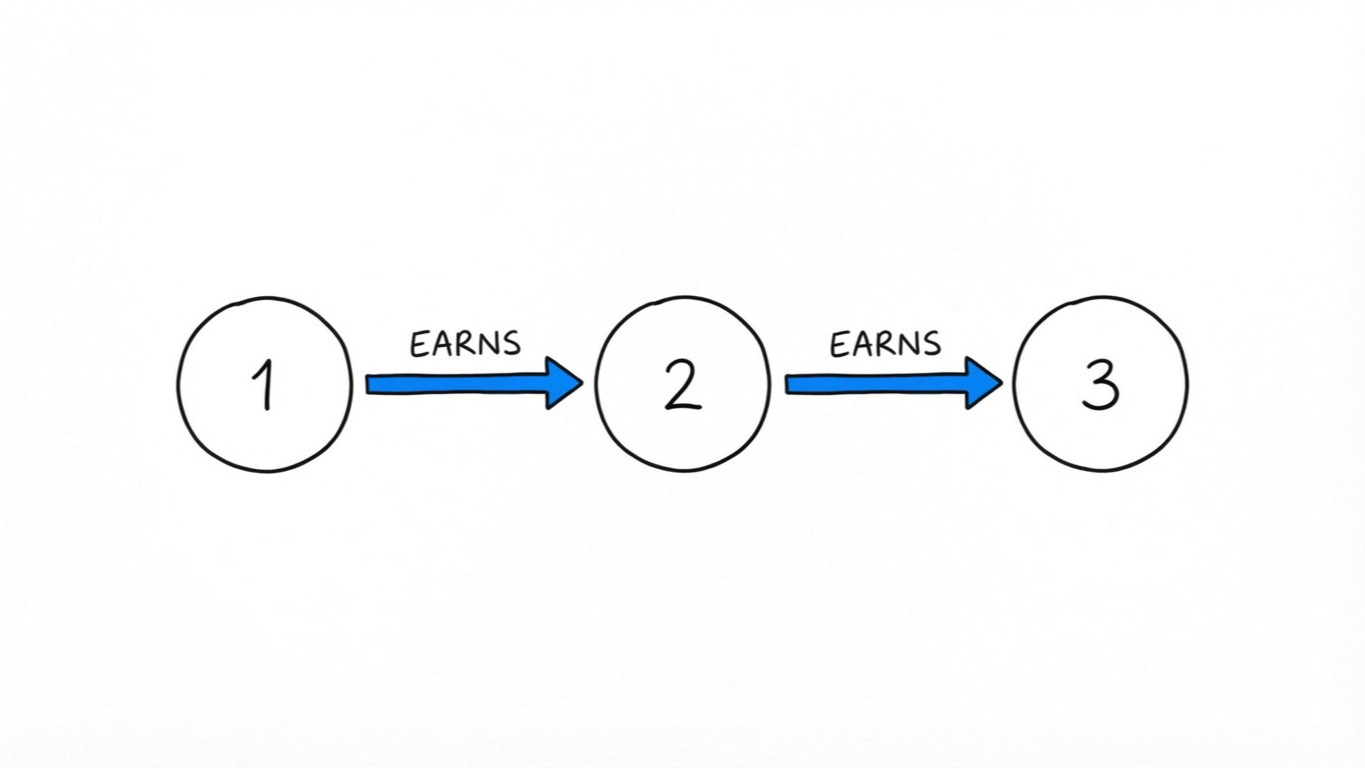

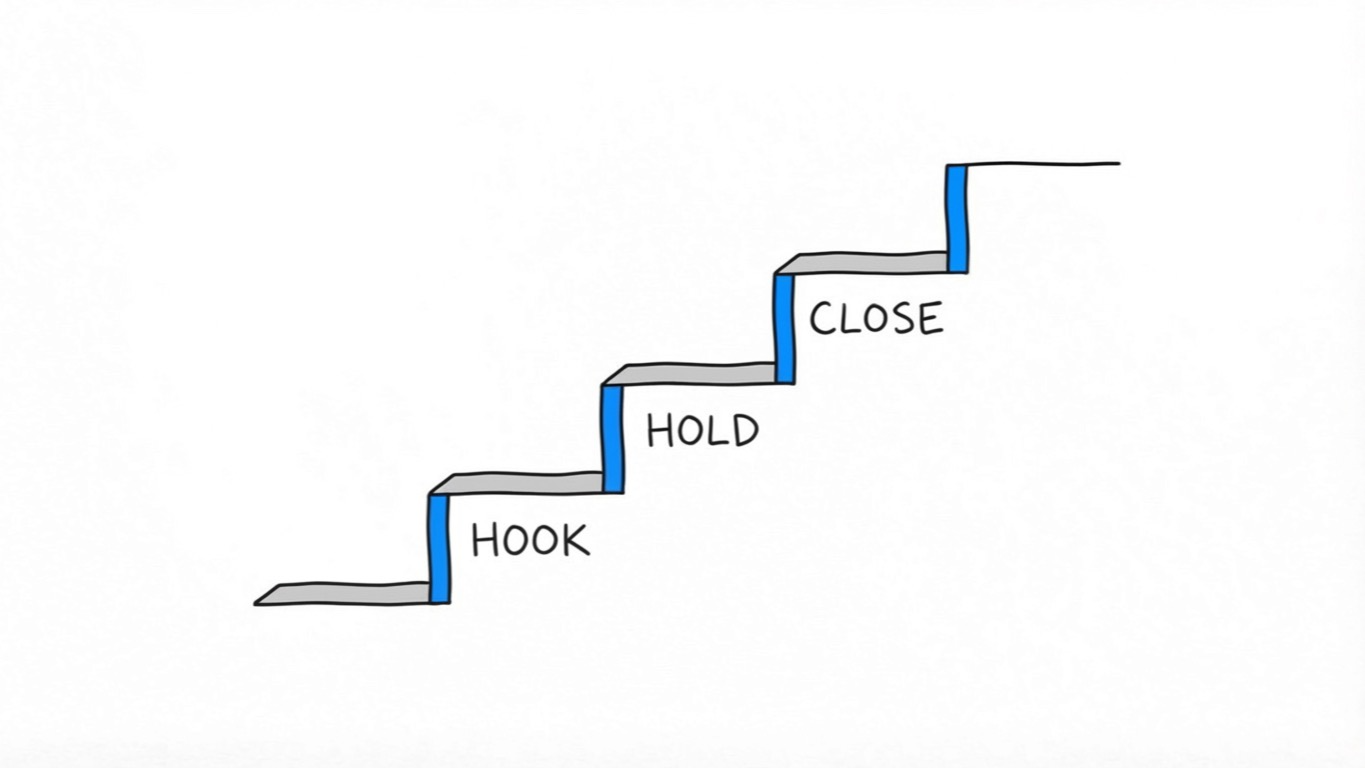

Dubin didn't sell razors in that video. He earned the right to sell them. Hook earns the right to Hold. Hold earns the right to Close.

Now watch someone skip the sequence.

Eight months before Dubin's video went live, Ron Johnson became CEO of JCPenney. Johnson had built the Apple Store. He knew retail.

His first move: eliminate 590 sales events per year. Replace them with "Fair and Square" pricing. Everyday low prices, no coupons, no manufactured urgency.

The logic was perfect. The sequence was wrong.

Johnson led with the close. Here's our price. Here's why it's fair. Here's where to buy.

No hook. No hold. No earned permission.

JCPenney lost $4.3 billion in revenue in a single year. Net losses hit $985 million. Johnson was fired after 17 months.

Johnson didn't have a pricing problem. He had a sequence problem.

Dubin earned the right to sell by making you laugh first. Johnson asked for the sale before earning the right to ask. Same era. Same retail. Opposite results. The difference was the order.

Now watch someone resurrect a dead product with nothing but sequence.

By 1985, Levi's 501 jeans were furniture. Your dad owned a pair. Maybe your grandfather. The brand meant reliable. And deeply uncool.

BBH, their London agency, didn't talk about denim. Didn't mention fit.

They showed a young man walking into a laundromat. He strips down to white boxer shorts. Puts his 501s in the machine. Sits down. A cover of Marvin Gaye's "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" plays.

Not a word about the product. Not a word needed.

501 sales rose 800%.

The ad didn't describe the jeans. It made you feel what it would be like to be the kind of person who wore them. Hook: the audacity of the scene. Hold: the unfolding performance. Close: the brand name on screen after the emotion had already done its work.

Sequence alone doesn't explain 800%. The casting, the song, the cultural moment all mattered. But none of it works if the ad opens with a price tag.

Three stories. One pattern.

Dubin hooked with humor, held with absurdity, closed with a subscription offer. 12,000 orders.

Johnson closed first. $4.3 billion gone.

Levi's hooked with audacity, held with desire, closed with a logo. 800% increase.

The mechanism isn't creative quality or pricing strategy or media spend.

It's sequence.

Hook earns attention. Hold earns desire. Close earns action. Skip a step, and the one after it fails.

The Perception Engine calls this the Vehicle System. The vehicle isn't the message. It's the sequence that earns you the right to deliver it.

Every failed campaign you've ever studied broke the same rule. Not the wrong message. The wrong sequence.

The vehicle delivers your message. But how do you know if it's working?

Most companies test the wrong things. Safe experiments that feel like progress but never create advantage. The Learn Loop shows where the real breakthroughs hide.

This is the third cylinder of The Perception Engine.