The Gate System

Why structured checkpoints save more lives than heroic intervention.

The 67% Problem

In American hospitals, something kills more patients than you'd expect.

Not cancer. Not heart disease. Not even medication errors in the traditional sense.

Handoffs.

When one doctor ends their shift and another begins. When a patient moves from the ER to the ICU. When a nurse hands off to the next nurse.

The Joint Commission found that 67% of serious medical errors involve handoff failures. Over a five-year period, inadequate handoffs contributed to 1,744 deaths and $1.7 billion in malpractice costs.

The information existed. The outgoing doctor knew the patient's allergies, the concerning lab result, the subtle change in vitals that worried them.

But the handoff failed.

And someone died.

The Same Mechanism

This is the same mechanism that killed 583 people at Tenerife.

The tower knew Pan Am was on the runway. Pan Am knew they hadn't exited. KLM's flight engineer asked if the runway was clear.

The information existed. It didn't flow.

In hospitals, the information exists in the outgoing doctor's head. It doesn't always reach the incoming doctor's hand.

The handoff is the danger zone.

Not because people are careless. Because handoffs are structurally difficult. Context doesn't transfer automatically. What seems obvious to someone who's been with a patient for eight hours isn't obvious to someone who just walked in.

The I-PASS Solution

In 2014, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine tested a structured handoff protocol called I-PASS.

The results:

- 23% reduction in medical errors

- 30% reduction in preventable adverse events

- No increase in handoff duration

I-PASS isn't complicated. It's an acronym that structures what you communicate:

| Letter | Meaning | Content |

|---|---|---|

| I | Illness severity | How sick is this patient? Stable, watcher, or unstable? |

| P | Patient summary | One-liner on why they're here |

| A | Action list | What needs to happen on your shift |

| S | Situation awareness | What might change? What should you watch for? |

| S | Synthesis by receiver | Receiver summarizes back, asks questions |

That's it.

A checklist. A structure. A gate.

Why It Works

I-PASS works because it removes ambiguity from the handoff.

Without I-PASS, a doctor might say: "Room 412 is a 68-year-old with pneumonia, doing okay, keep an eye on him."

With I-PASS:

- I: "Watcher. His oxygen has been borderline."

- P: "68-year-old with community-acquired pneumonia, day 3 of antibiotics."

- A: "Repeat chest X-ray in the morning. Call respiratory if O2 drops below 92."

- S: "He was confused earlier today. Could be early sepsis. Watch for fever."

- S: "So he's a watcher, pneumonia day 3, chest X-ray in AM, call RT if desat, and watch for confusion or fever as sepsis signs?"

Both handoffs contain information. Only one ensures it landed.

The receiver's summary is the gate check.

If they can't summarize accurately, the gate didn't pass. You try again.

Gates in Account Management

You don't work in a hospital. But you have the same structural problem.

Information exists in your head after a sales handoff, after a client discovery call, after a project kickoff. It needs to reach people who weren't there.

Without gates, the handoff is ambiguous. "The client wants more leads" could mean anything. It doesn't tell your SEO team what to optimize for or your PPC team what CPA target to hit.

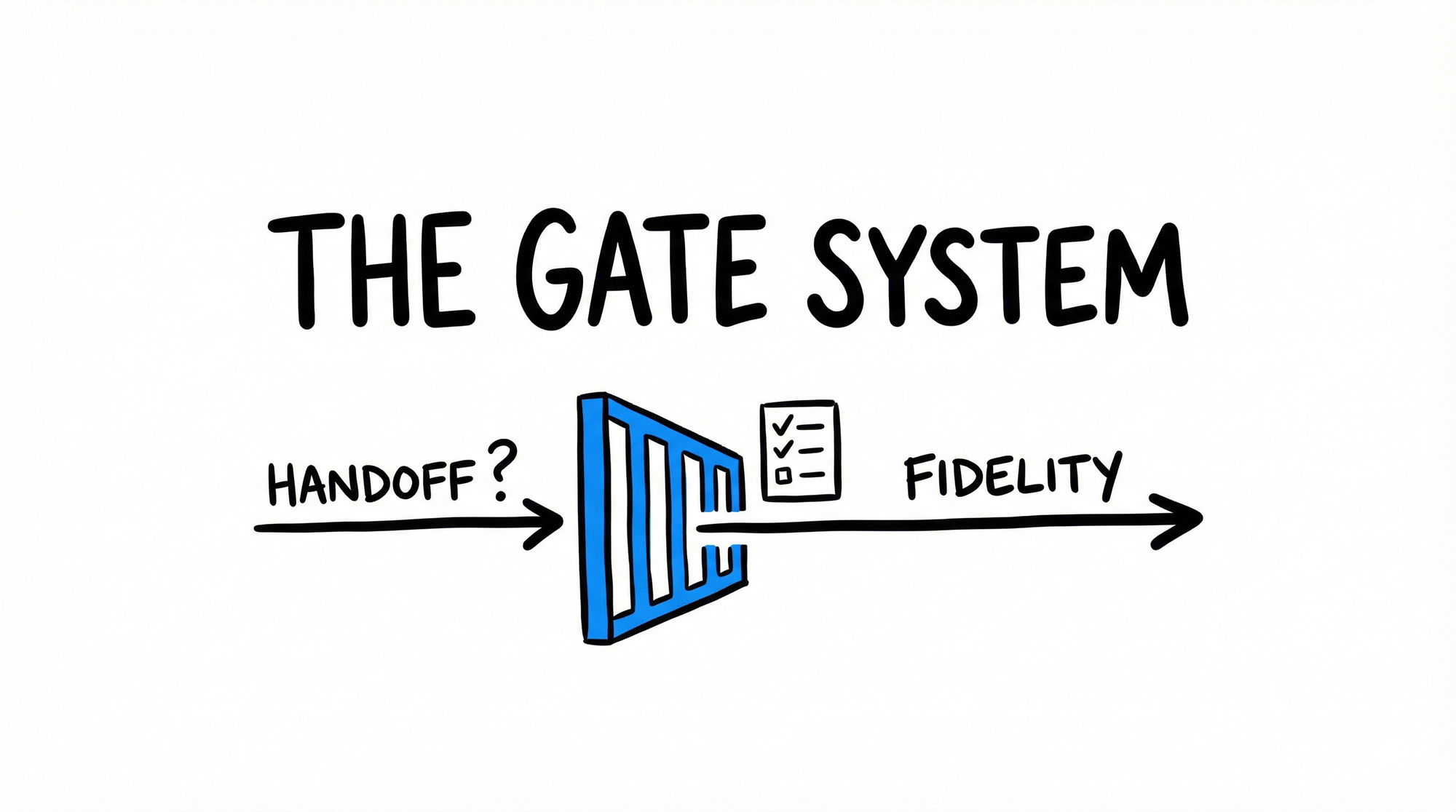

Gates force fidelity verification before work proceeds.

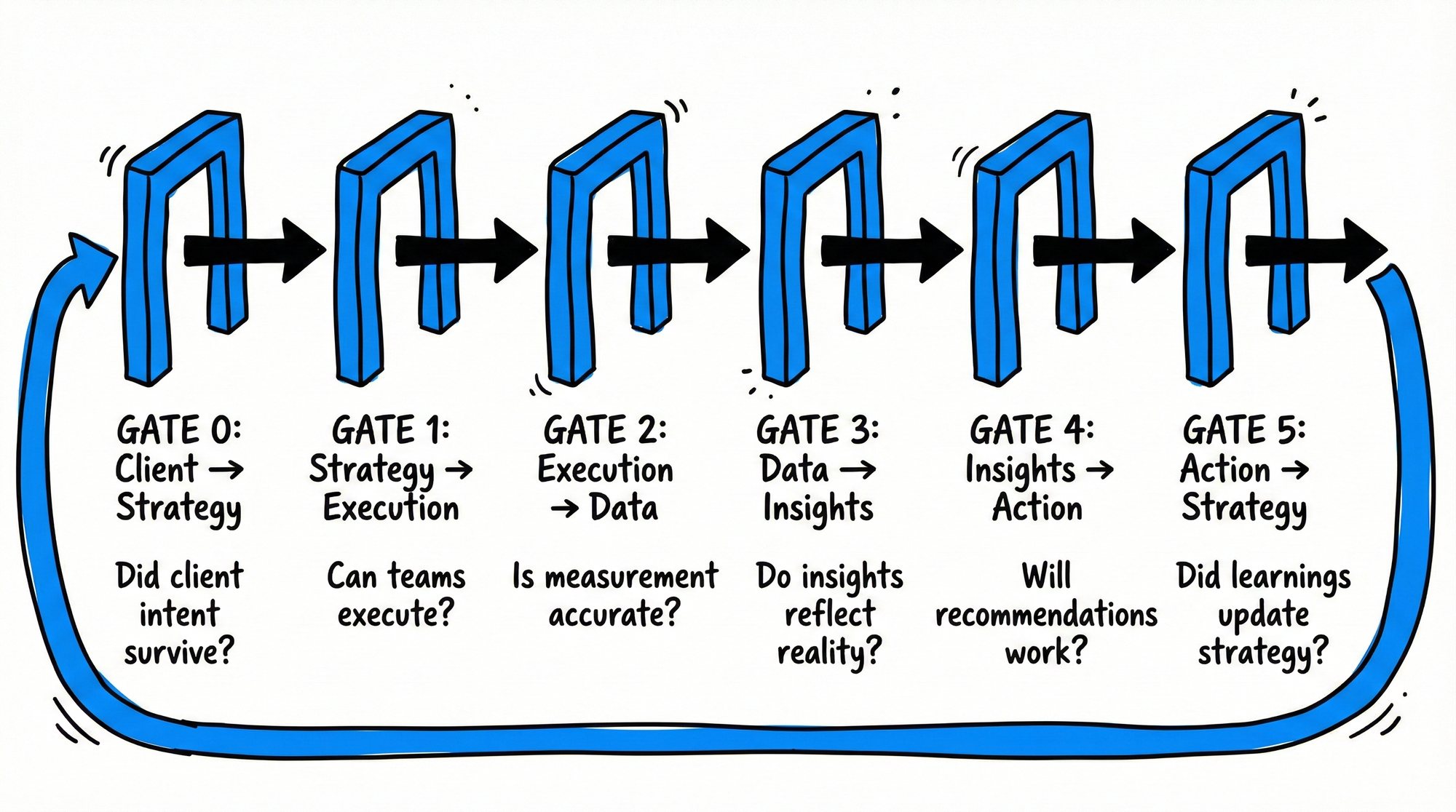

In the Information Flow cycle, we use six:

| Gate | Handoff | Fidelity Question |

|---|---|---|

| Gate 0 | Client → Strategy | "Did client intent survive the translation?" |

| Gate 1 | Strategy → Execution | "Can teams execute without clarification?" |

| Gate 2 | Execution → Data | "Is measurement capturing what matters?" |

| Gate 3 | Data → Insights | "Do insights reflect actual performance?" |

| Gate 4 | Insights → Action | "Will recommendations drive the right behavior?" |

| Gate 5 | Action → Strategy | "Did learnings update the strategy?" |

The cycle is continuous. Every arrow is a potential Tenerife.

The Gate 1 Test

Here's Gate 1's test:

Give your Story Anchor to someone on the execution team who wasn't in discovery. Ask them:

- "What problem is the client trying to solve?"

- "How will we know if we've succeeded?"

- "What should you NOT work on?"

If they can answer all three correctly, Gate 1 passes.

If they can't, you have an I-PASS failure. Information exists in your head. It hasn't reached theirs.

The solution isn't to lecture them. It's to fix the document.

Why "Later" Doesn't Work

The temptation is to skip the gate.

"I'll get that information later."

"We can always clarify as we go."

"The team knows how to ask questions."

This is the same logic that contributed to Tenerife. "Is he not clear, that Pan American?" "Oh yes."

The captain assumed. He was wrong. And there was no time to correct it.

In account management, the timeline is slower but the mechanism is identical. Incomplete handoffs create downstream failures that are expensive to fix.

A scope misunderstanding caught at Gate 1 is a 10-minute conversation.

The same misunderstanding caught at Gate 2 is a client fire drill.

Caught at Gate 3, it's a relationship at risk.

Gates feel slow in the moment. They create speed over time.

Building Your Gates

To implement gates:

1. Define the criteria. What specifically must be true before work proceeds?

2. Create the test. How will you verify the criteria are met? (The receiver summary is the gold standard.)

3. Hold the line. When criteria aren't met, work goes back upstream. No exceptions.

The last step is the hardest. The pressure to proceed is real. Deadlines exist. Clients are waiting.

But every time you let incomplete work through a gate, you're betting that downstream problems won't happen.

At Tenerife, that bet cost 583 lives.

In your work, it costs client trust, team morale, and your own time spent firefighting.

The Standard

Gates aren't bureaucracy. They're the infrastructure that makes good work possible.

I-PASS reduced medical errors by 23% without adding time. It didn't slow doctors down. It sped up the system by preventing rework.

Your gates can do the same thing.

Define the checkpoint. Test the handoff. Hold the line.

That's the gate system.

"67% of serious medical errors involve handoff failures. The information existed. It didn't flow."

This post explores the Gate System, the checkpoint mechanism from The Information Flow. Every handoff is a potential Tenerife.