The Jagged Frontier

AI passes the bar exam but can't count syllables. You can't predict from first principles where it will fail.

The Sonnet That Couldn't Count

GPT-4 can write a serviceable Shakespearean sonnet in seconds.

It understands iambic pentameter. Knows the rhyme scheme. Grasps the volta. Produces something that looks and feels like a sonnet.

Ask it to count the syllables in each line and it fails spectacularly. Eight syllables. Twelve syllables. Fourteen when there should be ten.

The same system that passed the bar exam in the 90th percentile cannot reliably count to fourteen.

This isn't a bug. It's a feature of how large language models work. And it tells you something essential about working with AI.

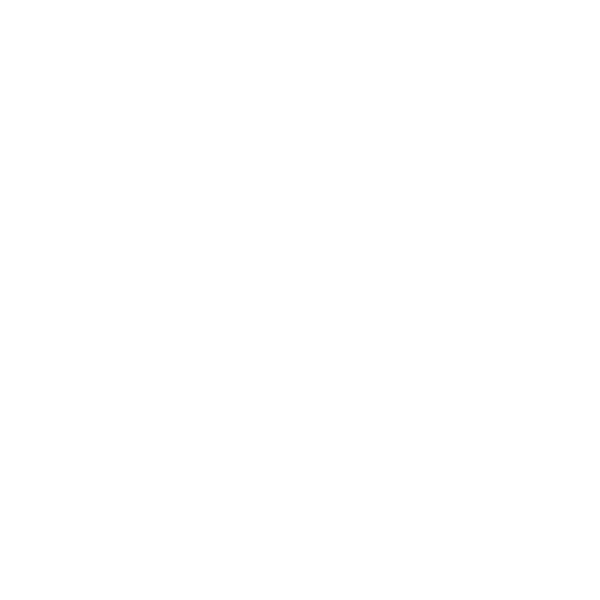

The Frontier Is Jagged

Imagine AI capability as a territory on a map.

The naive assumption is that this territory has a clean border. Easy tasks on one side. Hard tasks on the other. The harder the task, the more likely AI fails.

Reality looks nothing like this.

The actual border is jagged. Unpredictable. The frontier jumps in and out across complexity levels with no pattern a human could anticipate.

Ethan Mollick calls this the "jagged frontier": the irregular, constantly shifting boundary between what AI can and cannot do.

Some patterns:

AI diagnoses rare diseases better than most doctors. But hallucinates treatments that don't exist.

AI writes code that compiles and runs. But sometimes invents functions that no library contains.

AI summarizes complex documents accurately. But confidently includes facts that appear nowhere in the source.

AI solves PhD-level physics problems. But fails basic logic puzzles a child could answer.

The failures aren't random. But they're not predictable from first principles either.

Why Prediction Fails

Three forces create the jagged frontier:

1. Training Data Distribution

AI learned from what exists on the internet. Some domains are densely represented. Others are sparse. The density of training data doesn't correlate with task difficulty.

There's more text about legal reasoning than about counting syllables. Not because law is easier. Because lawyers write more.

2. The Compression Problem

Language models don't store facts. They compress patterns. Some patterns compress well. Others don't.

"14 syllables in a sonnet line" is a fact. Counting syllables requires decomposition the model wasn't trained to perform. The pattern recognition that makes AI brilliant at law makes it terrible at counting.

3. Emergent Capabilities

Nobody programmed GPT-4 to pass the bar exam. The capability emerged from scale and training. Emergent capabilities can't be predicted before they appear. And their boundaries can't be predicted after.

If the best AI researchers in the world can't predict where their models will fail, you certainly can't predict it from your office.

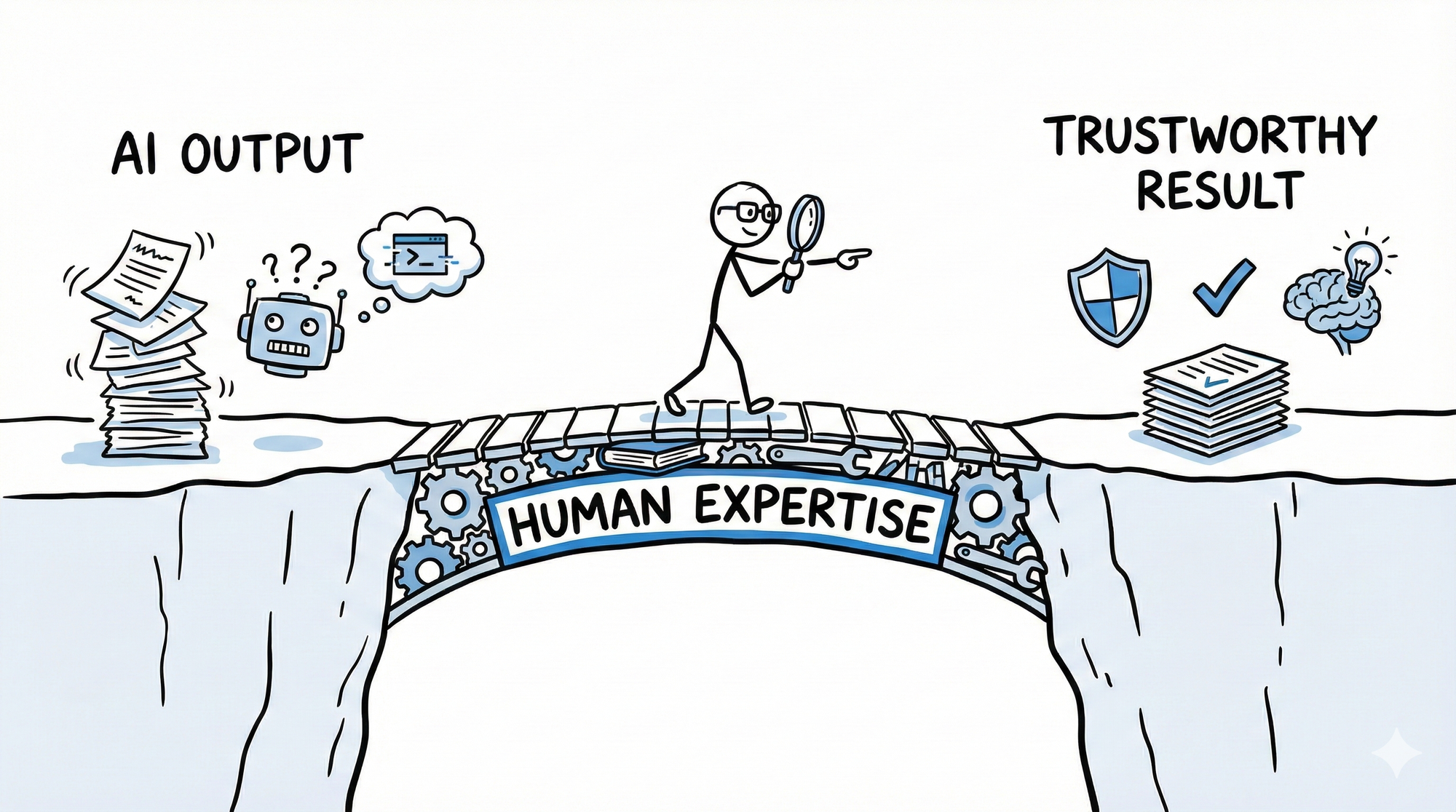

The Supervision Requirement

The jagged frontier creates a hard requirement: you need humans who can detect when AI fails.

This sounds obvious. It isn't.

If you can't predict where the failures are, you can't automate the checking. Every output needs evaluation by someone who knows the domain well enough to spot the subtle errors.

A lawyer who uses AI for research still needs to verify every citation. Not because citations are hard. Because the AI will confidently cite cases that sound real but don't exist.

A radiologist who uses AI for tumor detection still needs to review every scan. Not because detection is hard. Because the AI will miss the rare presentation that doesn't match its training data.

The jagged frontier means you can't fire the experts. You need them more, not less. Their job shifts from doing to supervising. But the expertise requirement doesn't decrease.

Mapping Your Edges

The only way to find the jagged edges is empirical. You have to test.

The Protocol:

- Pick a domain where you're considering AI

- Run it on 100 real examples from your actual work

- Have an expert evaluate every output, not just spot-check

- Document where it fails, not just where it succeeds

- Repeat quarterly - the frontier shifts

What you'll find:

The failures cluster in patterns. But they're patterns you wouldn't have predicted.

Maybe your AI handles complex queries well but fails on simple ones. Maybe it works perfectly on common cases but hallucinates on edge cases. Maybe it's reliable Monday through Thursday but degrades on Friday afternoon data.

You can't know until you test. And you can't stop testing because the frontier moves.

The Expertise Requirement

Here's the trap: the jagged frontier requires expertise to navigate. But AI's ease of use tempts organizations to skip the expertise.

"Just use ChatGPT" works until it doesn't. And when it doesn't, you need someone who can tell the difference between a good output and a confident hallucination.

That someone needs domain knowledge. Real expertise. The kind that takes years to develop.

Organizations that eliminate experts to cut costs don't just lose efficiency. They lose the ability to supervise the AI that replaced the experts.

The jagged frontier is why Path A works and Path B fails.

When humans provide context first, they're mapping the edges. Learning where AI works and where it doesn't. Building the judgment to supervise effectively.

When AI generates first, humans lose that map. They accept outputs without knowing which ones crossed the jagged line into failure territory.

The frontier is jagged. The only way to navigate it is expertise. The only way to build expertise is practice.

Same technology. Completely different safety profiles. The difference is who's doing the thinking.

"AI passes the bar exam but can't count syllables. The failures aren't random. But they're not predictable either. The only defense is expertise you're tempted to eliminate."

This post explores the Jagged Frontier, one of three dynamics from The Context Flow. You can't predict where AI fails. You have to test.