The Sincere Liar

The gap between what you say and what you do isn't hypocrisy. It's architecture.

Jonathan Haidt ran an experiment.

He asked people to read a story about a family who ate their dead dog. The dog was hit by a car. The family cooked it and ate it. Nobody got sick. Nobody found out.

Then he asked: Was this wrong?

Almost everyone said yes. Absolutely wrong. Disgusting. Immoral.

Then he asked: Why?

People struggled. They'd say it was unhealthy (but nobody got sick). They'd say it was disrespectful (but the dog was already dead). They'd say someone might find out (but nobody did).

Haidt would gently point out these contradictions. People would pause, think, then say: "I don't know, I can't explain it, but I just know it's wrong."

This is moral dumbfounding. You're certain. But you can't explain why.

The gap isn't dishonesty. It's architecture.

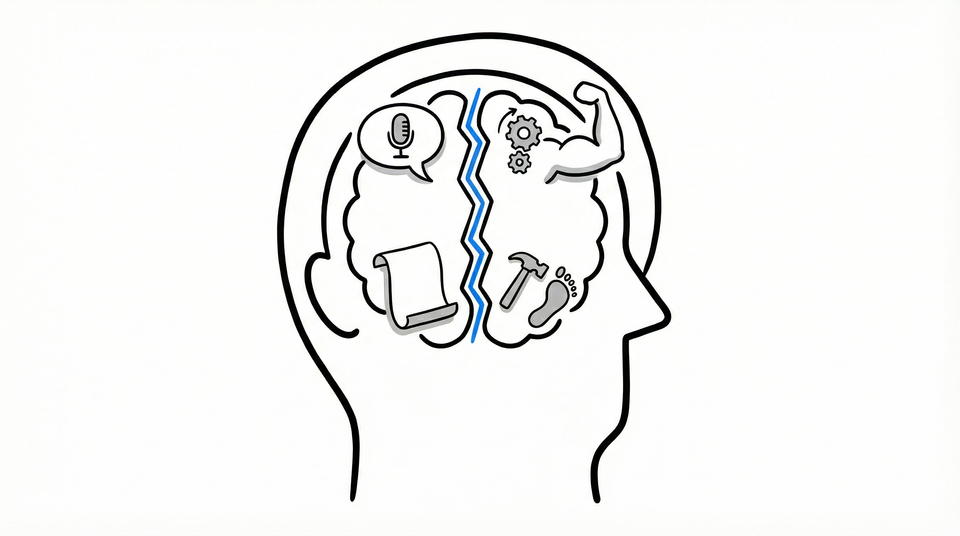

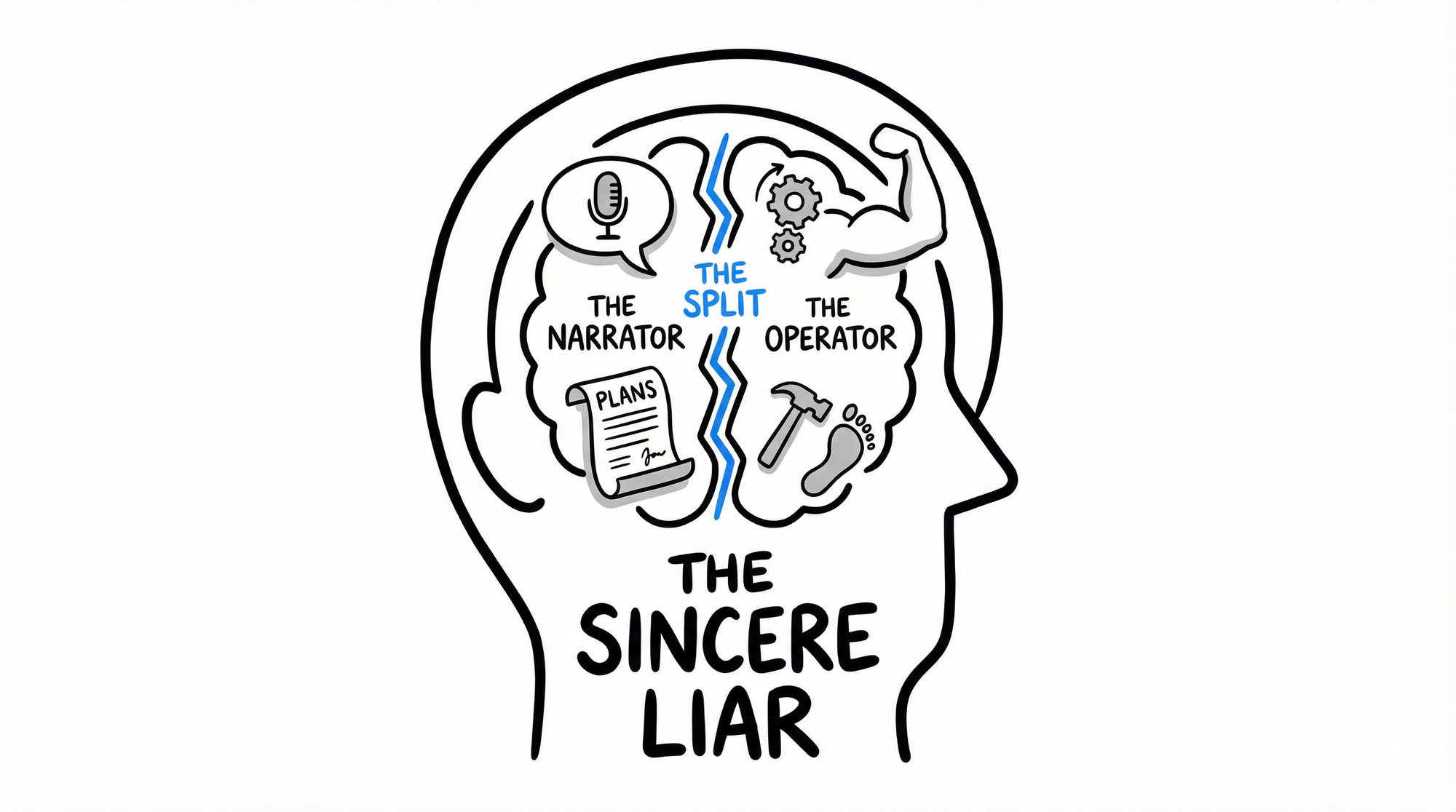

Your mind operates with two systems. One that acts. One that explains.

They're not the same system.

Jonathan Haidt offers the image: your mind is a rider on an elephant.

The rider (conscious, verbal self) thinks it's steering. It constructs narratives, explains decisions, articulates values.

But the elephant (intuitive, emotional, automatic self) is much bigger.

When rider and elephant disagree about where to go, the elephant wins.

The rider doesn't experience this as losing control. The rider experiences it as having made a reasonable decision, then constructs an explanation for why that decision aligned with stated values all along.

The rider is a press secretary, not a president.

Daniel Kahneman's research on System 1 and System 2 thinking reveals the same split.

System 1 (fast, intuitive, automatic) runs most of our behavior. It decides in milliseconds. It operates below conscious awareness.

System 2 (slow, analytical, deliberate) mostly endorses what System 1 already decided, then claims credit for the choice.

Your strategy deck is a System 2 document.

Your execution is System 1 in action.

No wonder they don't match.

Edgar Schein, studying organizational culture, identified three layers:

Artifacts: What you can see (office layout, dress code, meeting structure)

Espoused Values: What the organization says it believes (mission statements, values posters)

Basic Assumptions: What actually drives behavior (unspoken rules, real priorities)

The espoused values and basic assumptions are often different. And the organization is usually unaware of the difference.

Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) was one of the most successful computer companies of the 1970s and 80s. At its peak, it was the second-largest computer company in the world.

DEC's espoused values emphasized innovation, engineering excellence, and consensus decision-making.

But Schein, who studied DEC extensively, found different basic assumptions operating underneath: Engineers were gods. Sales and marketing were second-class citizens. Consensus meant endless debate. Innovation meant technical perfection, not customer needs.

These assumptions worked brilliantly when DEC was small and the market rewarded technical excellence.

They killed the company when the market shifted to personal computers and speed mattered more than perfection.

DEC's leadership genuinely believed in their espoused values. They just didn't see the basic assumptions driving actual behavior.

By 1998, DEC was sold to Compaq for a fraction of its former value.

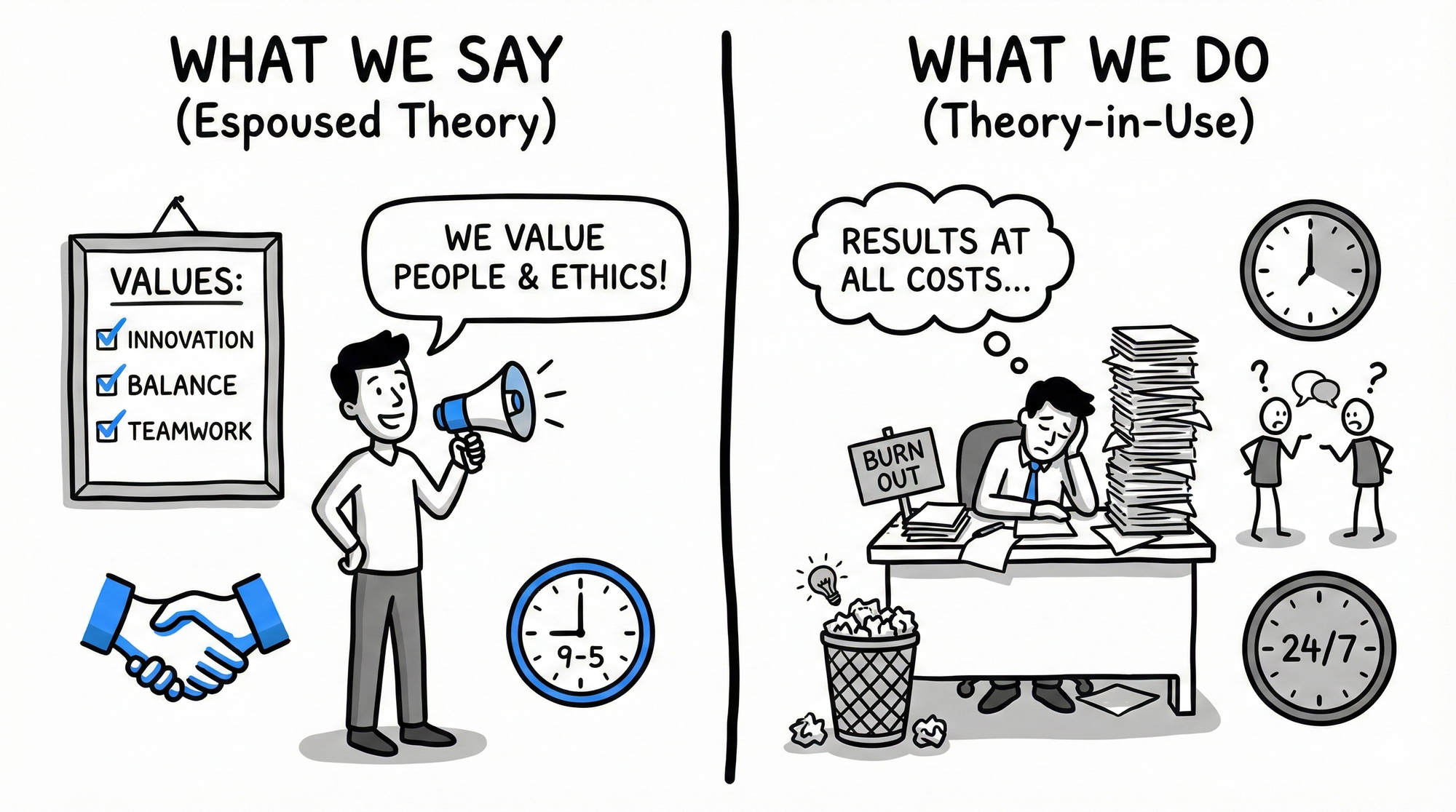

This isn't unique to organizations. You do this too.

You say you value work-life balance. Your calendar shows 60-hour weeks.

You say you want to be healthy. Your credit card shows fast food and skipped gym memberships.

You say you prioritize family. Your phone shows hours on social media and minutes with your kids.

You're not lying. Your Narrator genuinely believes what it's saying.

Your Operator is just following different instructions.

Chris Argyris spent decades studying this phenomenon. He gave the two theories names:

Espoused Theory: what we say we believe

Theory-in-Use: what our behavior implies we believe

The gap between them is invisible to the self. We experience our espoused theory as our actual theory. We construct explanations for why our behavior aligns with it, even when it doesn't.

Argyris called this "skilled incompetence." We're highly skilled at maintaining the illusion of alignment. We're incompetent at seeing the gap.

The diagnostic is simple but uncomfortable.

Don't ask what you believe. Ask what your behavior implies you believe.

If you spend 50 hours a week at work and 5 hours with family, your revealed belief is that work matters 10x more than family. Regardless of what you say you value.

If you fund the status quo and starve innovation, your revealed belief is that preservation matters more than growth. Regardless of what your strategy deck says.

If you promote people who hit numbers regardless of how, your revealed belief is that results matter more than methods. Regardless of what your values poster says.

The Narrator explains. The Operator reveals.

The fix isn't better narration. It's faster feedback.

Make the gap visible. Create mechanisms that surface theory-in-use. Reward people for pointing out divergence, not punishing them for it.

At Bridgewater Associates, Ray Dalio built "radical transparency" into the operating system. Every meeting recorded. Every decision documented. Disagreement required.

The architecture forces the gap into the open.

Does it work perfectly? No. The gap still exists. But it's visible, discussable, correctable.

You're not a hypocrite for having a gap between what you say and what you do.

You're a human with a Narrator and an Operator.

The question isn't whether you have a gap. Everyone does.

The question is whether you're willing to see it.

This post explores THE SPLIT, one of four forces from Execution Reveals. The Narrator articulates. The Operator acts. The gap between them isn't hypocrisy. It's architecture.