The Story Anchor

How to carry your client's voice into every room they're not in.

The Empty Chair

Jeff Bezos has a habit that confuses new Amazon employees.

At important meetings, he leaves an empty chair. No one sits in it. No one moves it. It just sits there, taking up space.

The chair represents the customer.

"The most important person in the room."

This isn't sentiment. It's not symbolic leadership theater. It's an information solution.

When decisions are made without the customer's perspective, they're made on assumptions. The empty chair forces each discussion to answer a question that wouldn't otherwise get asked: "How does the customer experience this?"

In one documented incident, Bezos called Amazon's customer service line during an executive meeting. His team had presented data on response times. Bezos wanted to verify it.

The data was wrong.

The chair doesn't represent feelings about customers. It represents information the room doesn't naturally have.

The Problem You're Solving

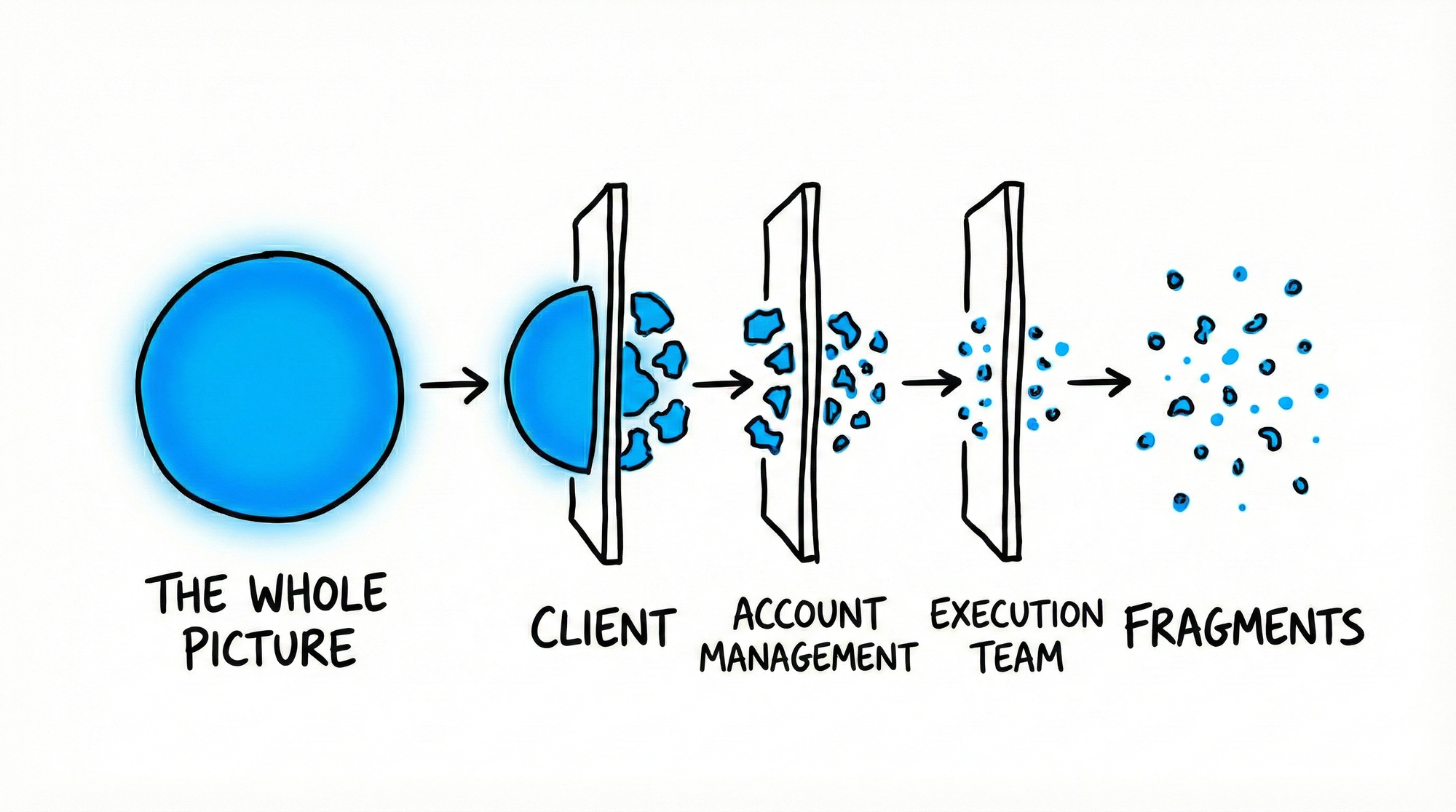

You have a discovery call with your client.

For an hour, you learn why they hired you. What keeps them up at night. What success looks like. What's out of scope. Who the stakeholders are. What politics exist under the surface.

That conversation lives in your head.

Then the SEO team asks: "What should we optimize for?"

You answer. But you're translating from memory. You compress, summarize, interpret. Context gets lost.

Then the content team asks: "What tone should we use?"

You answer again. More compression. More loss.

Then the PPC team asks: "What's our target CPA?"

You're now repeating yourself in slightly different ways to different people. Each team gets a fragment of what you know. No one gets the whole picture.

The client's actual question gets diluted across every handoff.

This is the same mechanism that killed 583 people at Tenerife. The tower knew Pan Am was on the runway. Pan Am knew they hadn't exited. The information existed in the system. It just wasn't in the KLM cockpit.

Your teams are the KLM cockpit. They're making decisions. They don't have the full picture. And you can't be on every call, in every room, at every decision point.

What the Story Anchor Does

The Story Anchor is Bezos's empty chair for client relationships.

It's a document that travels with the work. Not stored in a folder somewhere. Not filed and forgotten. Actively referenced. Present in rooms where you're not.

It captures the SCQA:

- SITUATION: Where is the client now? What's the baseline?

- COMPLICATION: What's blocking them? Why now? What happens if nothing changes?

- QUESTION: What do they actually need answered? (Not "what did they ask for" — what's the real strategic question?)

- ANSWER: Your hypothesis. Your approach. Why you believe it will work.

Plus the operational details:

- SUCCESS METRICS: How the client defines winning. Not how we define it.

- CHANNEL ROLES: What each service contributes to the answer.

- SCOPE BOUNDARIES: What's IN and what's OUT.

When the PPC team asks about target CPA, they don't just get a number. They see why that number matters to the client's actual business goal. They understand the context.

The Story Anchor is how client intent survives the handoffs.

The Fragmentation Problem

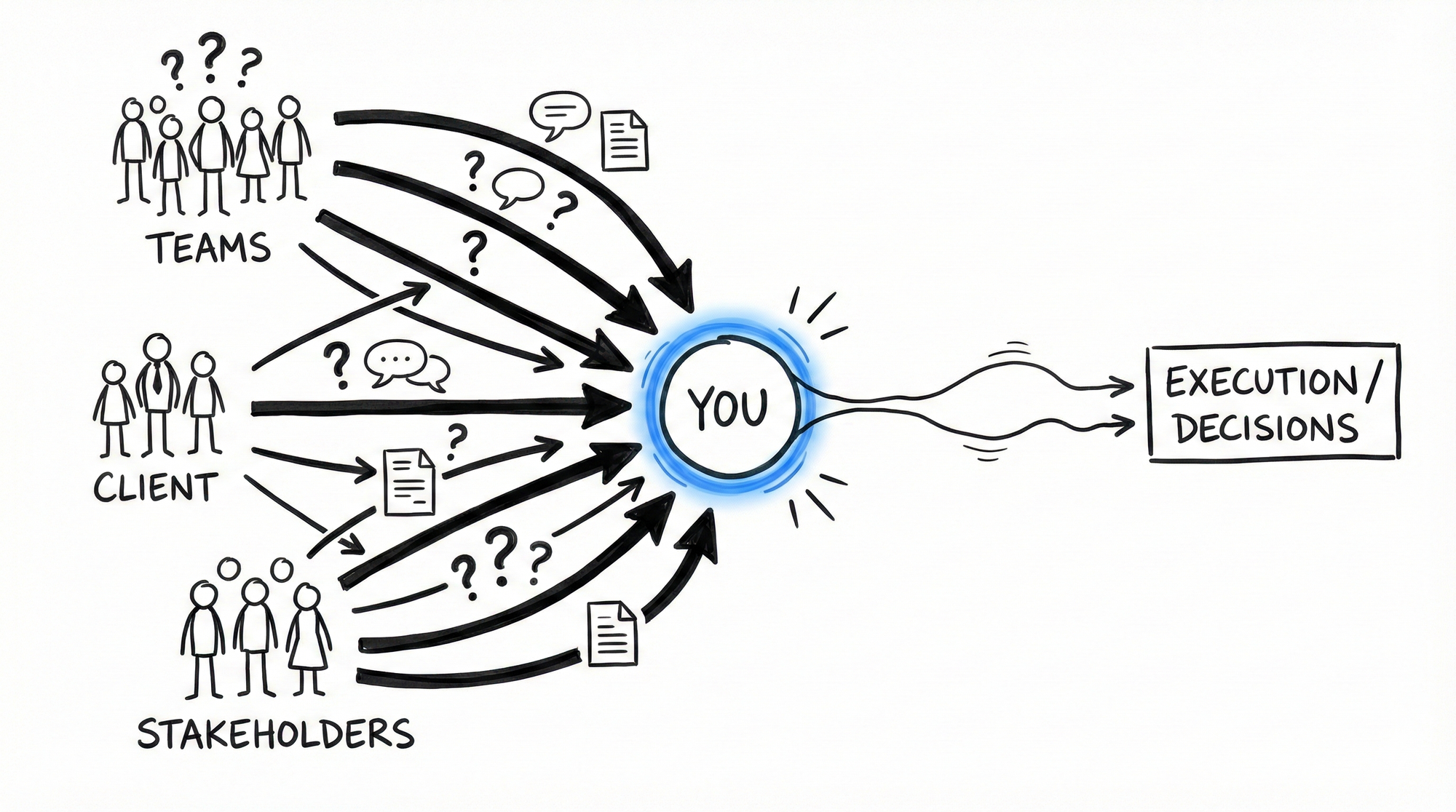

Without a Story Anchor, you become the single point of failure.

Every question routes through you. Every decision requires your context. Every pivot needs your translation.

This doesn't scale. And it creates risk.

What happens when you're on vacation? When you're sick? When you're in back-to-back meetings and can't respond?

Teams either wait (and miss deadlines) or guess (and miss the target).

The Story Anchor distributes context. It means any team member can pick up the document and understand what the client actually needs — not just what task they were assigned.

It's the difference between "do this task" and "here's why this task matters."

Situation, Complication, Question, Answer

The SCQA structure comes from Barbara Minto's Pyramid Principle. McKinsey has used it for decades to structure strategic communication.

Here's why it works for Story Anchors:

Situation

The baseline. Context that everyone needs to know before anything else makes sense.

"Client X is a B2B SaaS company selling to enterprise IT departments. They currently generate 40% of leads through paid search, 30% through organic, and 30% through events. Their average deal size is $50K with a 6-month sales cycle."

Complication

The tension. What's changed, what's threatening, what opportunity exists.

"Their paid search CPL has increased 40% year-over-year while conversion rates have declined. Meanwhile, a new competitor is outranking them on their core product terms. The board is asking why marketing efficiency is declining."

Question

The real strategic question. Often different from what the client initially asked.

"How do we reduce dependency on paid search while protecting lead volume during the transition?"

Note: The client might have asked "improve our SEO." The Question is the strategic problem underneath that request.

Answer

Your hypothesis and approach.

"Shift budget from branded PPC (losing efficiency) to content + SEO (building owned assets). Protect volume short-term by focusing PPC on highest-intent, lowest-competition terms. Success metric: maintain lead volume while reducing overall CPL by 20% over 6 months."

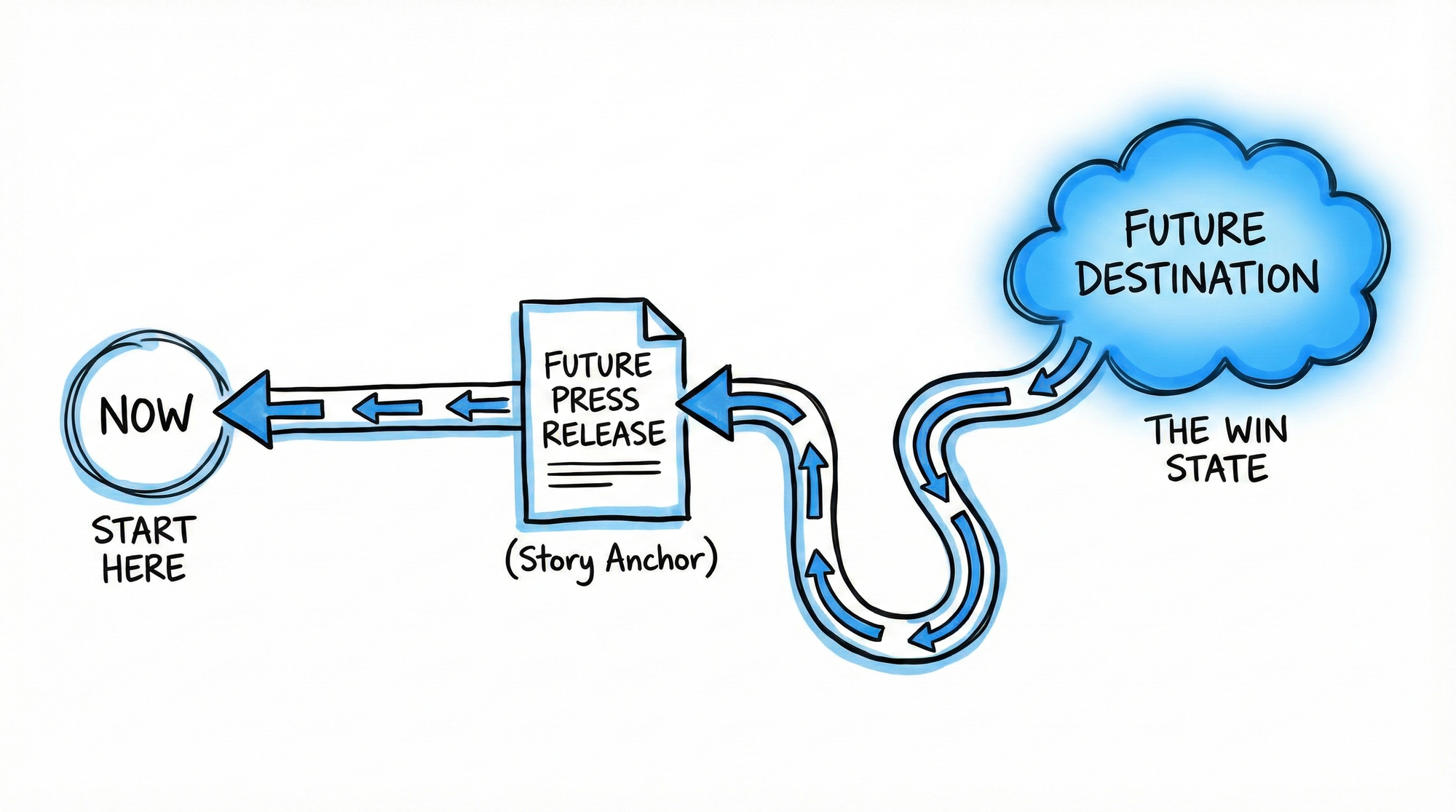

The Future Press Release

Bezos has a second practice that completes the empty chair.

The chair represents who the customer is now. But Amazon teams also need to see where the customer is going.

So before Amazon builds anything, product teams write a press release. Not after launch. Before development begins.

The press release describes the product as if it already exists and succeeded. It answers:

- Who is this for?

- What problem does it solve?

- How does the customer benefit?

- What does success look like?

If the team can't write a compelling press release, the product isn't ready to build.

This is "working backwards." Start with the end state. Define the destination clearly. Then figure out how to get there.

The Story Anchor should work the same way.

SCQA captures the current reality. But your teams also need to see the future. What does the world look like when this engagement succeeds?

Add a section to your Story Anchor:

The Win State

"Six months from now, Client X is generating 50% more leads than today at 20% lower cost. They've reduced paid search dependency from 40% to 25% of leads. Their board sees marketing as an asset, not a cost center. The client has promoted the marketing director who championed this strategy."

This isn't a promise. It's a destination.

When teams can visualize the win — not just the tasks — they make better decisions. They understand which tradeoffs serve the destination and which undermine it.

The empty chair represents the client in the room. The future press release represents where the client is trying to go.

The Test

Here's how you know if your Story Anchor is working:

Give it to someone on the execution team who wasn't in discovery.

Ask them three questions:

- "What problem is the client trying to solve?"

- "How will we know if we've succeeded?"

- "What should you NOT work on?"

If they can answer all three correctly, your Story Anchor is doing its job.

If they can't, your client's voice isn't reaching the people doing the work. You have an empty chair, but no one knows who's supposed to be sitting there.

Story Anchor vs. Brief

A brief describes deliverables.

A Story Anchor describes intent.

| Brief | Story Anchor |

|---|---|

| "Write 10 blog posts" | "Build organic visibility for purchase-intent keywords" |

| "Set up conversion tracking" | "Enable attribution across the 6-month sales cycle" |

| "Create landing pages" | "Reduce friction in the trial-to-paid conversion" |

Briefs answer: "What do you want us to make?"

Story Anchors answer: "What are you trying to accomplish, and why?"

Teams with briefs execute tasks. Teams with Story Anchors make decisions.

When something goes wrong — when a stakeholder changes priorities, when the market shifts, when a deliverable doesn't land — teams with Story Anchors can adapt. They know the destination. They can find a new route.

Teams with only briefs have to call you. Every time.

Keeping It Alive

A Story Anchor isn't a one-time document.

It evolves. As you learn more about the client, as strategy shifts, as stakeholders change, the Story Anchor updates.

The rule: If something is true about the client that affects how teams should work, it belongs in the Story Anchor.

New stakeholder with different priorities? Update the Story Anchor.

Scope boundary clarified? Update the Story Anchor.

Success metric changed? Update the Story Anchor.

The document is a living record of client context. Not a snapshot. A stream.

The Standard

Your client can't be in every room.

But their voice can. And their destination can.

Bezos solved this with two practices:

The empty chair represents who the customer is now. Their current reality. Their context.

The press release represents where they're trying to go. The future state. The destination.

Your Story Anchor combines both. It carries your client's voice AND their vision into every room they're not in.

Document the now. Define the destination. Let the work serve both.

"The chair shows who they are. The press release shows where they're going. The Story Anchor carries both."

This post explores the Story Anchor, the intent preservation mechanism from The Information Flow. Your client's voice travels into every room they're not in.