The Upstream Principle

Why fixing early prevents failures late, and where you should focus your attention.

The Safety Speech

In 1987, Paul O'Neill became CEO of Alcoa, the world's largest aluminum producer.

Investors expected a turnaround speech. The company was struggling. They wanted to hear about cost-cutting, market share, new products.

O'Neill walked to the podium and said: "I want to talk to you about worker safety."

The room went quiet.

"Every year, numerous Alcoa workers are injured so badly that they miss a day of work. Our safety record is better than the general American workforce, but it's not good enough. I intend to make Alcoa the safest company in America. I intend to go for zero injuries."

One investor in the audience reportedly called his clients immediately after and told them to sell their stock. "The board put a crazy hippie in charge."

He was wrong.

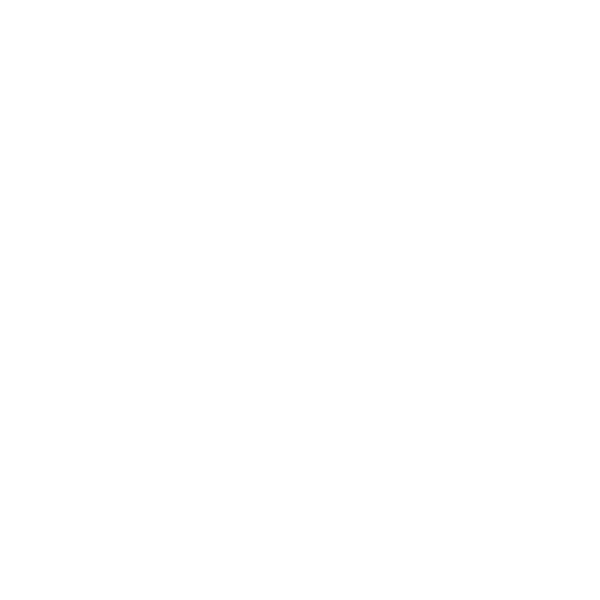

The Upstream Insight

O'Neill understood something the investors didn't:

Safety is a leading indicator of operational excellence.

To achieve zero injuries, you can't just post safety posters and give speeches. You have to examine every production process. You have to understand why accidents happen and fix the root causes.

Those root causes are upstream. They're in the design of the processes, the training of the workers, the communication between shifts, the maintenance of equipment.

Fix upstream, and downstream improves.

If you eliminate the conditions that cause injuries, you simultaneously eliminate the conditions that cause defects, delays, and waste. The same sloppy handoff that leads to a worker getting hurt also leads to a batch getting ruined.

O'Neill's bet was simple: if Alcoa became obsessive about safety, they would become obsessive about process. And obsessive process excellence would show up in the financials.

The Results

By the time O'Neill retired in 2000:

- Alcoa's market value grew from $3 billion to $27 billion

- Annual net income increased from $200 million to $1.48 billion

- Lost workdays due to injury dropped from 1.86 to 0.2 per 100 workers

The "crazy hippie" had made Alcoa one of the safest AND most profitable companies in America.

O'Neill later said: "If you want to know if Alcoa is moving forward, check our safety record. Safety is a leading indicator of financial performance."

The thing everyone dismissed as distracting from the real work WAS the real work.

What This Means for You

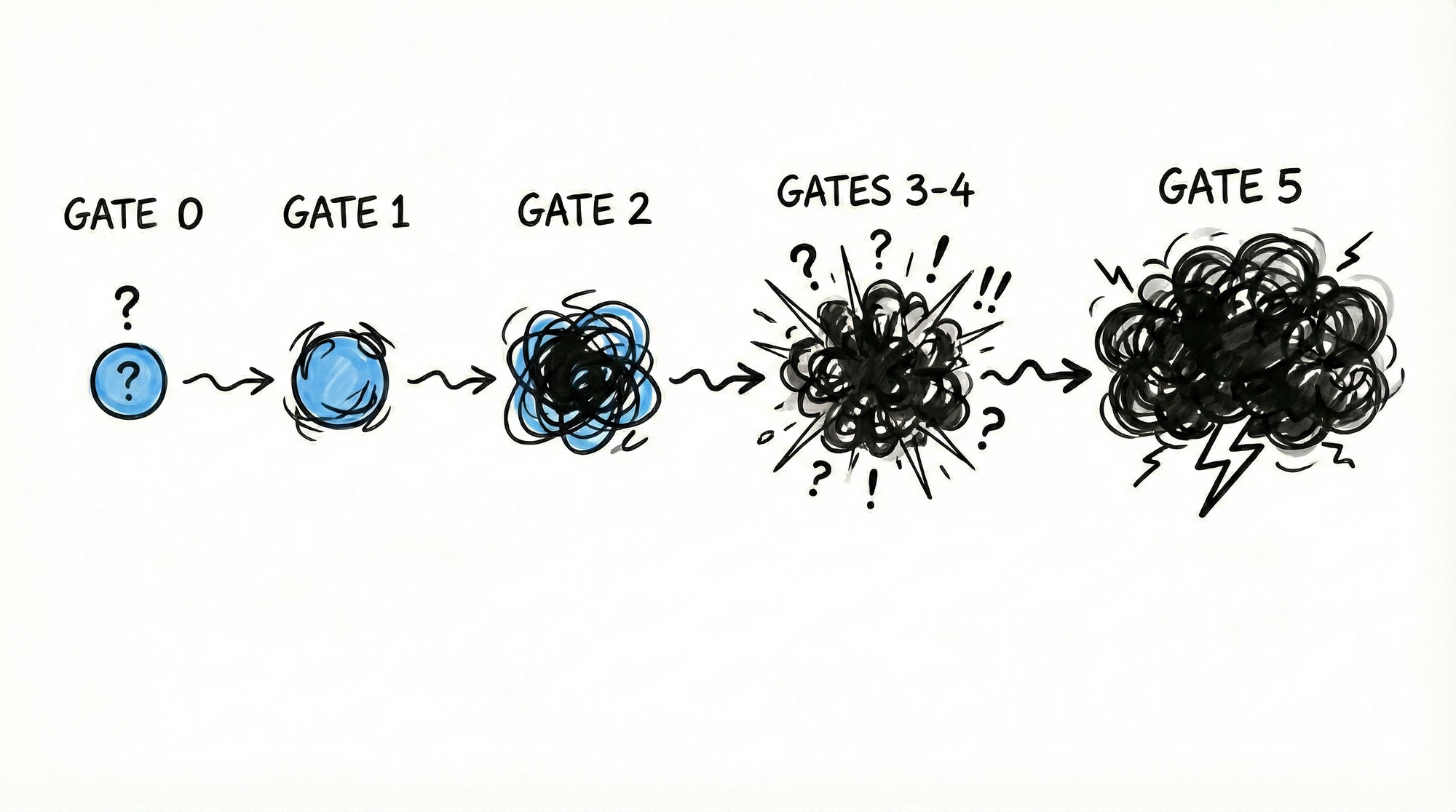

In account management, your upstream is the early gates in the information cycle:

- Gate 0: Client → Strategy. Did intent survive translation?

- Gate 1: Strategy → Execution. Can teams execute without clarification?

Your downstream is everything that follows:

- Gate 2: Measurement accuracy

- Gates 3-4: Insights and recommendations

- Gate 5: Learning loops back to strategy

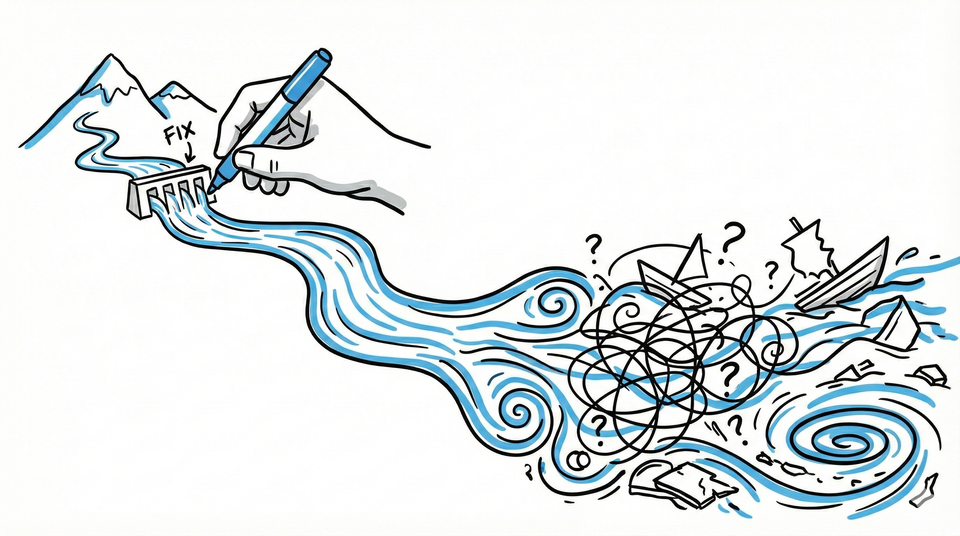

Problems at Gates 0-1 cascade through the entire cycle.

When sales doesn't transfer complete context, your strategy starts from scratch. When your strategy doesn't capture real success criteria, execution teams optimize for the wrong thing. When teams miss the target, you spend hours in damage control.

O'Neill's insight applied to information flow: If you get the early handoffs right, everything downstream becomes easier.

The Visibility Problem

Here's the trap:

Upstream work is invisible. Downstream firefighting is heroic.

Nobody celebrates the account that renewed smoothly because you asked the right questions in the first week. Nobody notices the crisis that never happened because the sales handoff was complete.

But when you save an account that was about to churn? When you personally step in to resolve a client escalation? That's visible. That gets recognized.

This creates a dangerous incentive.

You appear more valuable when putting out fires than when preventing them. Firefighting is dramatic. Prevention is boring.

But prevention is where the leverage lives. An hour spent at Gate 0 prevents ten hours of rework at Gate 3.

O'Neill understood this. He made safety metrics the first thing discussed in every meeting. He made prevention visible by measuring it obsessively.

Making Upstream Visible

O'Neill's move was to make the invisible visible.

He required that any injury, anywhere in Alcoa's global operations, be reported to him within 24 hours. Not to punish anyone. To learn.

The reporting requirement accomplished two things:

- It signaled priority. When the CEO personally reviews every safety incident, everyone understands that safety matters.

- It created feedback loops. Each incident was analyzed, root causes were identified, and changes were made to prevent recurrence.

In your work, you can do the same:

Make early gate fidelity visible. Track how complete sales handoffs are. Measure how often teams need clarification after strategy. Create feedback loops that reveal fidelity loss before it becomes a downstream crisis.

The question isn't whether fidelity problems exist. They always do.

The question is whether you've built the systems to see them early.

The O'Neill Test

Here's a diagnostic:

When something goes wrong with a client — a missed expectation, a deliverable that didn't land, a relationship that soured — trace it backwards.

Ask: Where did this problem actually start?

Usually, the answer is upstream. A misunderstanding at kickoff. A success metric that was never clarified. A stakeholder whose priorities weren't captured.

The downstream symptom gets all the attention. But the upstream cause is where the fix lives.

O'Neill looked at every injury and asked: "What process allowed this to happen?"

You can look at every client fire drill and ask: "What handoff failed?"

Two Kinds of AMs

There are AMs who spend their days in meetings, managing crises, smoothing over misunderstandings, being the irreplaceable connector between client and team.

And there are AMs whose accounts run smoothly, whose teams rarely need clarification, whose clients renew without drama.

The difference isn't talent. It's where they invest their attention.

The first type is downstream-focused. They're constantly in motion, constantly needed, constantly visible.

The second type is upstream-focused. They're less visible, less heroic, less dramatic. But their clients are better served.

O'Neill could have spent his tenure running from crisis to crisis. Instead, he fixed the system that created the crises.

The Standard

O'Neill shocked investors by talking about safety instead of profits.

He understood that safety wasn't separate from profits. It was the leading indicator. Fix the upstream system and the downstream results follow.

In your work, the upstream is Gates 0 and 1. The strategy handoff. The context transfer. The Story Anchor.

Invest your best attention there.

The fire drills you're managing today started with fidelity loss last month. The smooth accounts you're not thinking about succeeded because someone got the early gates right.

Fix upstream. Downstream improves.

That's the principle O'Neill proved at Alcoa. It works the same way in information flow.

"If you want to know if Alcoa is moving forward, check our safety record. Safety is a leading indicator of financial performance." — Paul O'Neill

This post explores the Upstream Principle, the prevention leverage from The Information Flow. Fix early, prevent late.