Proactive Stance

Why telling clients about problems before they discover them builds more trust than hiding them.

The Recall

In the fall of 1982, seven people in the Chicago area died.

The cause: Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules laced with potassium cyanide. Someone had tampered with bottles on store shelves.

Johnson & Johnson faced a nightmare scenario. Their flagship product — accounting for 17% of the company's income — was killing people. And they had no way of knowing how widespread the contamination was.

The contamination, as it turned out, was limited to the Chicago area. Maybe a few dozen bottles at most.

But Johnson & Johnson didn't know that at the time. Neither did the public.

CEO James Burke had a choice:

Option A: Wait. Investigate. Limit the recall to confirmed contamination zones. Manage the message carefully.

Option B: Recall everything. All 31 million bottles of Tylenol capsules nationwide. Immediately. At a cost exceeding $100 million.

He chose B.

The recall was excessive. The contamination was local. Most of those 31 million bottles were perfectly safe.

It was also exactly right.

The Asymmetry

Here's what Burke understood:

A customer discovering poisoned pills would destroy the brand.

The company announcing a recall — even an excessive one — would preserve trust.

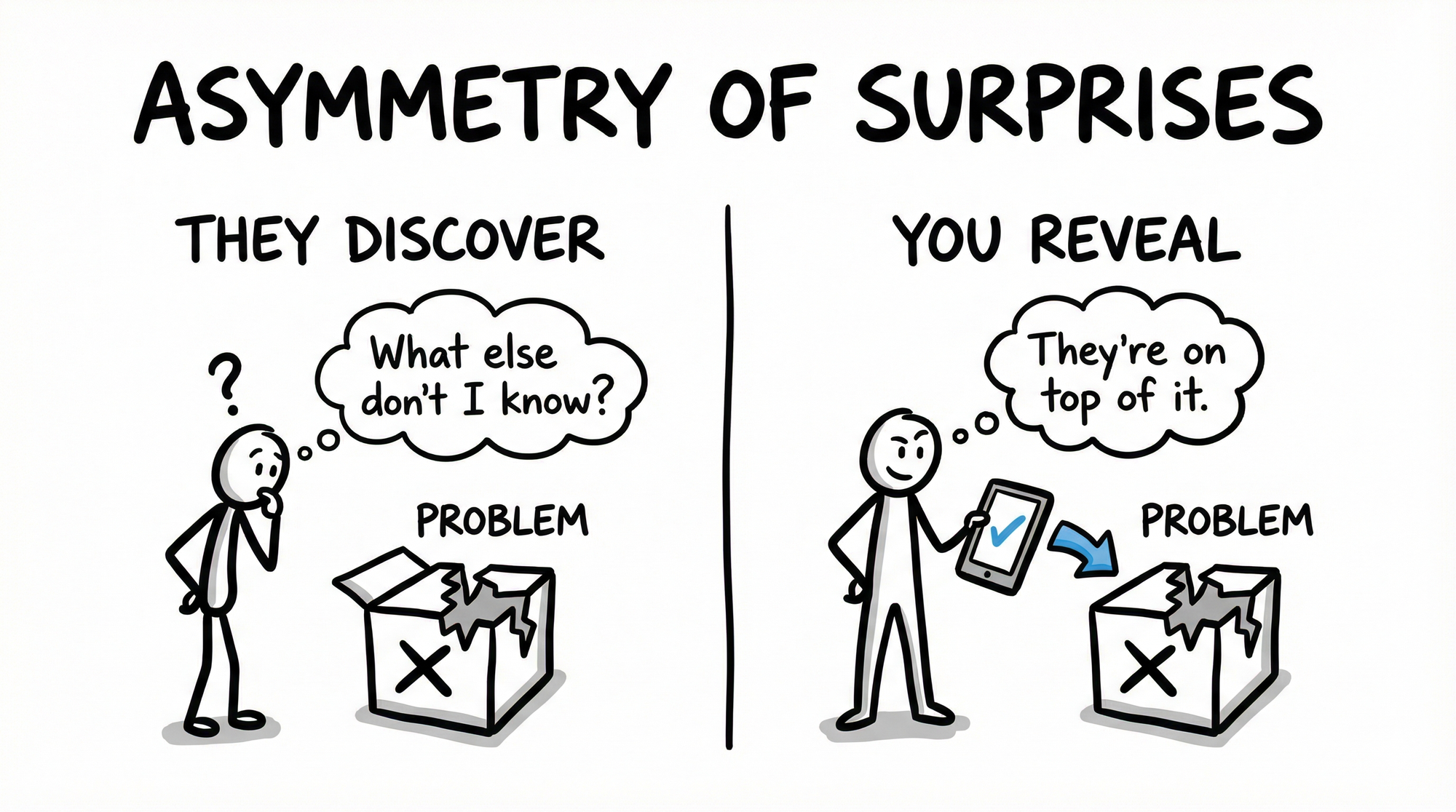

This is the asymmetry of surprises:

| Who Discovers First | Client Thinks |

|---|---|

| Client discovers problem | "What else don't I know?" |

| You communicate problem | "They're on top of it." |

The same information, delivered by different parties, creates opposite outcomes.

When you tell a client about a problem, you're demonstrating control. You know what's happening. You're managing it. You have a plan.

When a client discovers a problem you knew about, you're demonstrating negligence. You knew and didn't tell them. What else are you hiding?

The problem itself becomes secondary to who owned the narrative.

Why We Hide

The instinct to hide problems is understandable.

You don't want to alarm the client unnecessarily. You're already working on a fix. By the time you explain it, you'll have the solution. Why create anxiety?

This logic feels solid. It's also wrong.

Here's what actually happens when you hide:

- You don't fix it as fast as you thought

- The client notices something's off

- They ask a question you weren't ready for

- Now you're explaining why you didn't mention it earlier

- The original problem is now compounded by trust erosion

The fix that was supposed to take a day takes a week. The small issue becomes a relationship issue.

Hiding doesn't remove the risk. It just delays it while adding stakes.

The Tenerife Connection

At Tenerife, Pan Am's copilot transmitted: "We're still taxiing down the runway!"

He was communicating proactively. Warning the KLM aircraft. Trying to prevent disaster.

KLM didn't hear it. The message was blocked by overlapping radio transmissions.

In your work, you have advantages Pan Am didn't have:

- Multiple channels (email, phone, Slack, video)

- The ability to confirm receipt

- Time to structure your message

You can make sure your communication gets through.

The Pan Am copilot tried to be proactive. You have the ability to actually succeed at it.

The 24-Hour Rule

Here's a simple practice:

Any significant negative development gets communicated to the client within 24 hours.

Not fixed within 24 hours. Communicated.

"I want to let you know that we discovered a tracking issue yesterday. Here's what happened, here's what we're doing about it, and here's when you'll hear from me next."

That's it. Three sentences.

The client now knows:

- You're aware of the problem

- You have a plan

- They can expect an update

The update matters more than the fix at this stage. The fix restores performance. The update restores confidence.

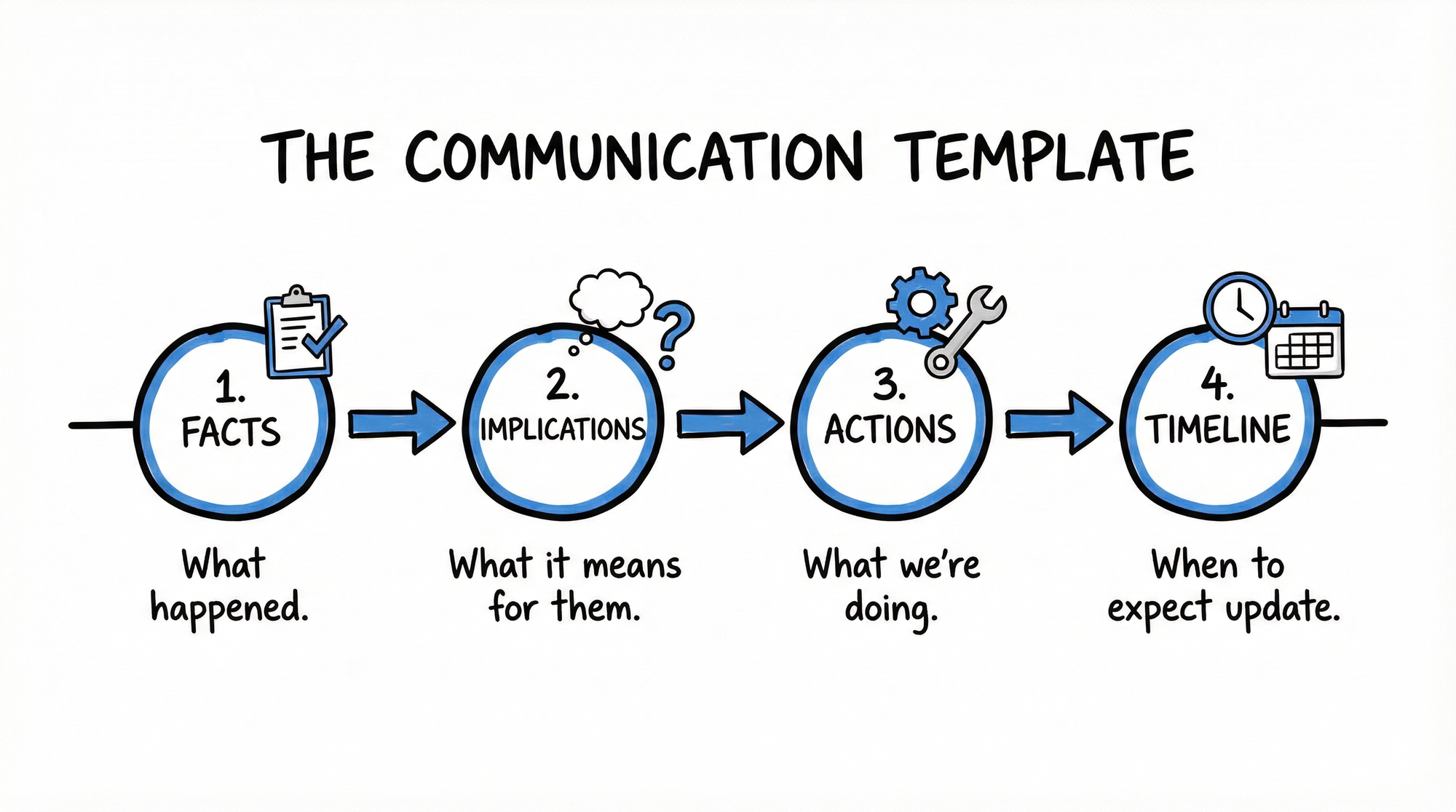

The Template

When you need to communicate bad news, use this structure:

1. What happened. Brief, factual, no spin. "We discovered that conversion tracking was misconfigured for the past two weeks."

2. What it means. Implication for them. "This means the conversion data in your dashboard for that period isn't accurate."

3. What we're doing. Action plan. "We're reconstructing the data from backup sources and will have corrected numbers by Friday."

4. When you'll hear next. Timeline for follow-up. "I'll send you an update by Thursday with initial findings."

No apology wallowing. No over-explanation. No blame-shifting.

Facts, implications, actions, timeline.

The structure signals competence. You understand what happened. You're managing it. The client can trust you're on it.

Tylenol's Recovery

Here's what happened after the recall:

Within a year, Tylenol recovered over 90% of its market share.

The contamination wasn't Johnson & Johnson's fault. Someone had poisoned products on store shelves. The company was a victim.

But they didn't position themselves as victims. They positioned themselves as proactive protectors of their customers.

They introduced tamper-evident packaging (now an industry standard).

They offered free replacements and coupons.

They communicated constantly, transparently, directly.

The recall that cost $100 million bought trust that couldn't be purchased any other way.

The Cost of Reactive

What would have happened if Burke had chosen Option A?

Imagine a customer in Detroit buying Tylenol after hearing about Chicago deaths. Maybe contamination had spread. Maybe it hadn't. Nobody knew.

If that customer got sick — or even just felt uncertain — the brand would never recover.

The proactive recall eliminated that possibility. It said: "We are protecting you, even at enormous cost to ourselves."

Reactive crisis management always costs more than proactive communication.

In your work, the same math applies. The tracking issue you hide today becomes the client escalation next month. The underperformance you massage in reports becomes the renewal loss next quarter.

The cost of proactive is a difficult conversation now.

The cost of reactive is all of that plus trust erosion plus relationship repair plus potential contract loss.

No Surprises in Meetings

Here's an extension of the 24-hour rule:

If there's bad news, the client knows before any scheduled meeting or report.

Never let the monthly review be where they learn something went wrong. Never let the QBR reveal underperformance they didn't expect.

The meeting should be about what we're doing about the problem, not about discovering the problem exists.

When clients are surprised in meetings, they can't respond thoughtfully. They're processing emotion while you're trying to discuss strategy. The meeting goes sideways.

When they already know, they've had time to process. The meeting becomes productive.

Own the narrative before the room gathers.

The Standard

Johnson & Johnson didn't recall 31 million bottles because they were legally required to.

They did it because they understood the asymmetry:

Proactive bad news builds trust. Reactive bad news destroys it.

In your work, the problems are smaller but the principle is identical.

Tell clients about problems before they discover them. Communicate within 24 hours. No surprises in meetings.

The temporary discomfort of delivering bad news is nothing compared to the permanent damage of being discovered hiding it.

Own the narrative. Tell them first. Build the trust that lasts.

"J&J didn't recall Tylenol because they were responsible for the poisoning. They recalled it because letting customers discover the problem would cost more than any recall ever could."