The Doer's Advantage

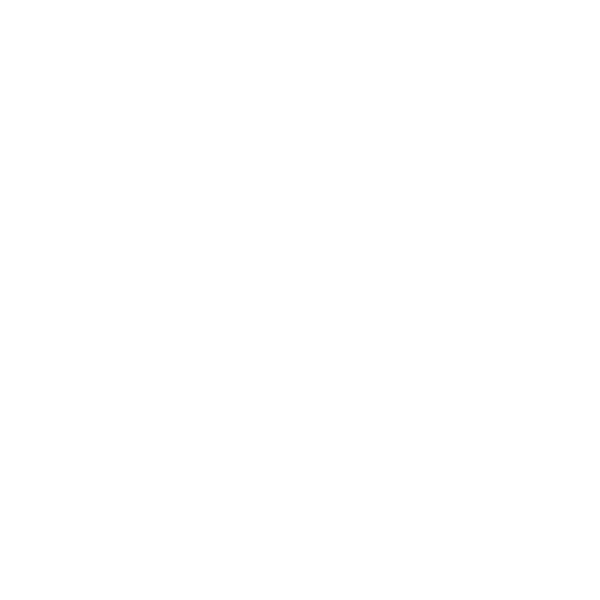

What happens to this person if they're wrong? That question separates knowledge from opinion.

In 2008, Wall Street analysts predicted the financial crisis with 0% accuracy.

The ones who saw it coming? Michael Burry, who bet his fund. John Paulson, who bet his reputation.

They didn't have better models. They had skin in the game.

There are two kinds of knowledge in the world.

One comes from analysis. The other comes from action.

The analyst studies the market. The investor bets on it.

The consultant designs the strategy. The operator implements it.

The critic reviews the restaurant. The chef runs the kitchen.

We treat these as equivalent expertise.

They're not.

Nassim Taleb calls this the problem of the "Intellectual Yet Idiot." The IYI gets first-order logic right but misses second-order effects. They can explain why something should work. They can't feel when it's about to break.

This isn't about intelligence. Many advisors are brilliant.

It's about a fundamental asymmetry in how knowledge gets created.

The advisor faces no consequences for being wrong. The bad recommendation becomes a learning opportunity, a case study, a footnote.

The doer faces all the consequences. The bad decision becomes a loss, a failure, a scar.

One of these creates knowledge. The other creates opinions.

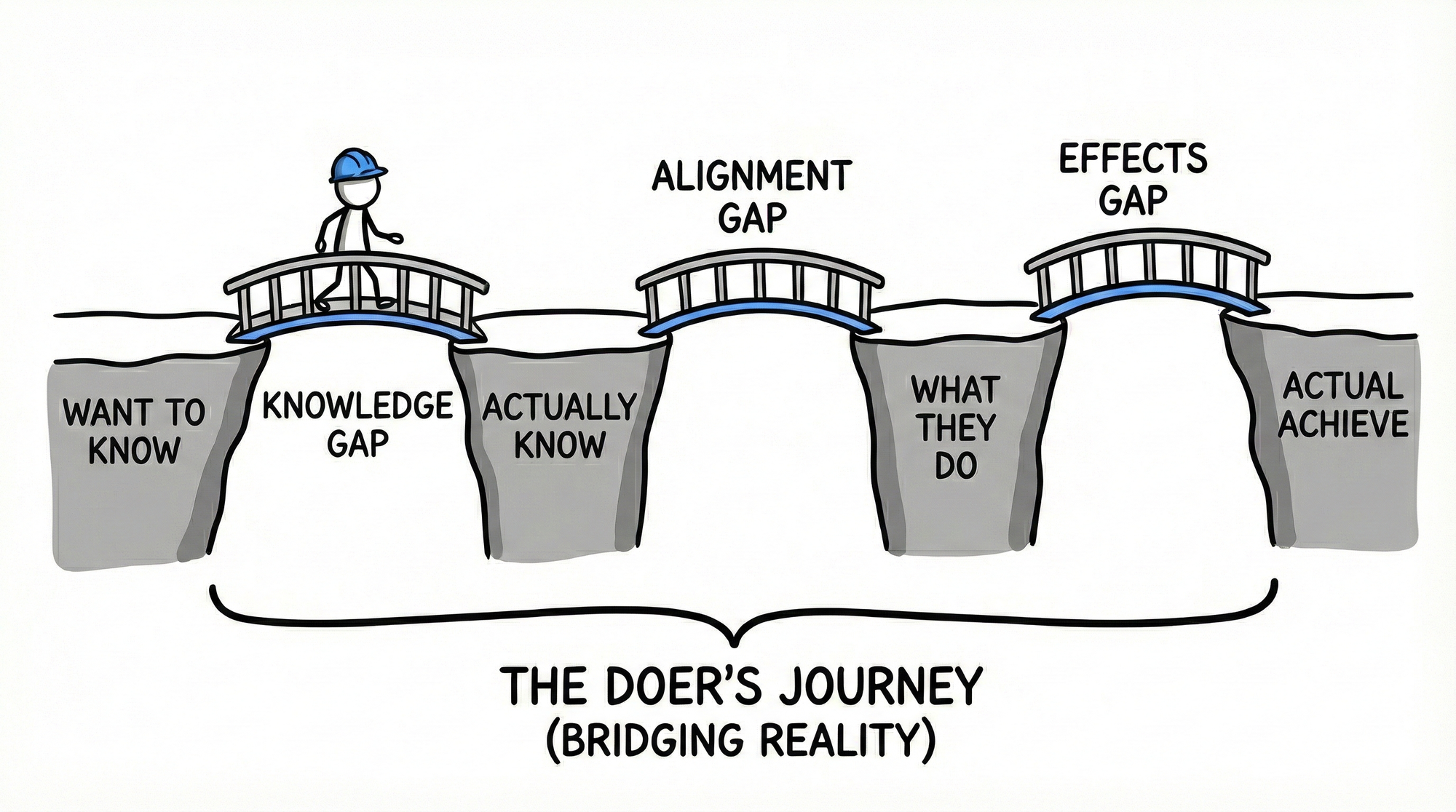

Stephen Bungay, studying why strategies fail to become results, identified three gaps between intention and outcome:

The Knowledge Gap: between what we'd like to know and what we actually know

The Alignment Gap: between what we want people to do and what they actually do

The Effects Gap: between what we hope our actions achieve and what they actually achieve

Advisors never encounter these gaps. They operate in a world where plans are clean, execution is assumed, and results match intentions.

Doers live in all three gaps simultaneously.

The knowledge gap teaches them what they don't know. The alignment gap teaches them how organizations actually behave. The effects gap teaches them how reality responds to their best-laid plans.

This learning rewires intuition. The doer develops pattern recognition that the advisor never acquires because the advisor's mental models are never stress-tested by consequences.

Carl von Clausewitz called this "friction." The countless minor incidents that combine to make the simple very difficult.

Plans never encounter friction. They exist in a frictionless fantasy where everything goes according to expectation.

Execution lives in friction every moment.

The friction is where the learning happens.

The track record of professional market forecasters tells the story.

Studies analyzing thousands of predictions found that "experts" predicting market direction achieved 47% accuracy. Less than random chance.

Abbey Joseph Cohen, formerly chief U.S. investment strategist at Goldman Sachs, achieved 35% accuracy. Jim Cramer, CNBC fixture and former hedge fund manager: 46.8%.

These are people paid millions to predict markets.

Warren Buffett doesn't predict markets at all. He buys businesses. He holds them. He faces the consequences of being wrong.

"The only value of stock forecasters," Buffett wrote, "is to make fortune tellers look good."

Berkshire Hathaway has compounded at nearly 20% annually since 1965. The S&P 500: 10.4%. The difference over six decades: 5,502,284% versus 39,054%.

The forecasters have more data, more models, more PhDs.

They have no skin in the game.

Buffett has less certainty but more consequences. He admits he "can't predict the short-term movements of the stock market" and hasn't "the faintest idea as to whether stocks will be higher or lower a month or a year from now."

The forecasters claim certainty they don't have. Buffett admits uncertainty but acts anyway.

One approach creates knowledge. The other creates noise.

Remember the surgical checklist story from the pillar. Surgeons resisted a two-minute checklist despite evidence showing 36% fewer complications and 47% fewer deaths.

The surgeons weren't wrong to value their judgment. They had spent decades building embodied knowledge through consequences. Every patient outcome shaped their intuition. Every complication refined their pattern recognition.

The checklist came from advisors who had studied surgery but never performed it. The surgeons' resistance wasn't just ego. It was a legitimate suspicion that people without skin in the game were telling them how to do their jobs.

Where they went wrong was confusing the source of knowledge with its validity. The checklist was created by non-doers, but it was validated by outcomes. The data was undeniable.

The doer's advantage is real. But it's not absolute.

The doer develops judgment that the advisor never acquires. The advisor can sometimes see patterns that the doer is too close to notice.

The mistake is treating advice as equivalent to execution-tested knowledge.

It rarely is.

When evaluating expertise, ask one question:

What happens to this person if they're wrong?

The consultant moves to the next engagement. The executive loses their job.

The analyst writes another report. The investor loses their capital.

The politician gets re-elected. The citizen lives with the policy.

This asymmetry is everywhere. It's why execution reveals truth that advice never can.

Talk is cheap because nothing happens when you talk. Doing is expensive because reality resists.

The resistance is where knowledge gets created.

Don't ask what someone thinks. Ask what they've done. And ask what happened when they were wrong.

That's where the real expertise lives.

This post explores THE MIRROR, one of four forces from Execution Reveals. Words have no consequences. Actions produce outcomes. This asymmetry is why execution reveals truth that planning hides.