When Abundance Becomes Enemy

If you can't name what you're NOT doing, you don't have a strategy. You have a wish list.

In 2010, SoftBank gave WeWork $4.4 billion.

Then another $6 billion. Then another $2 billion.

The money kept coming. WeWork kept spending. Office space in 280 cities. Private jets. A wave pool company. A coding academy. Unlimited free beer.

Nobody asked the hard question: Does the unit economics work?

They didn't have to. There was always more money.

By 2019, WeWork was worth $47 billion on paper. Six weeks later, the IPO collapsed. The company was worth $8 billion. SoftBank lost $13 billion.

Unlimited capital obscured a simple truth: WeWork was losing money on every lease.

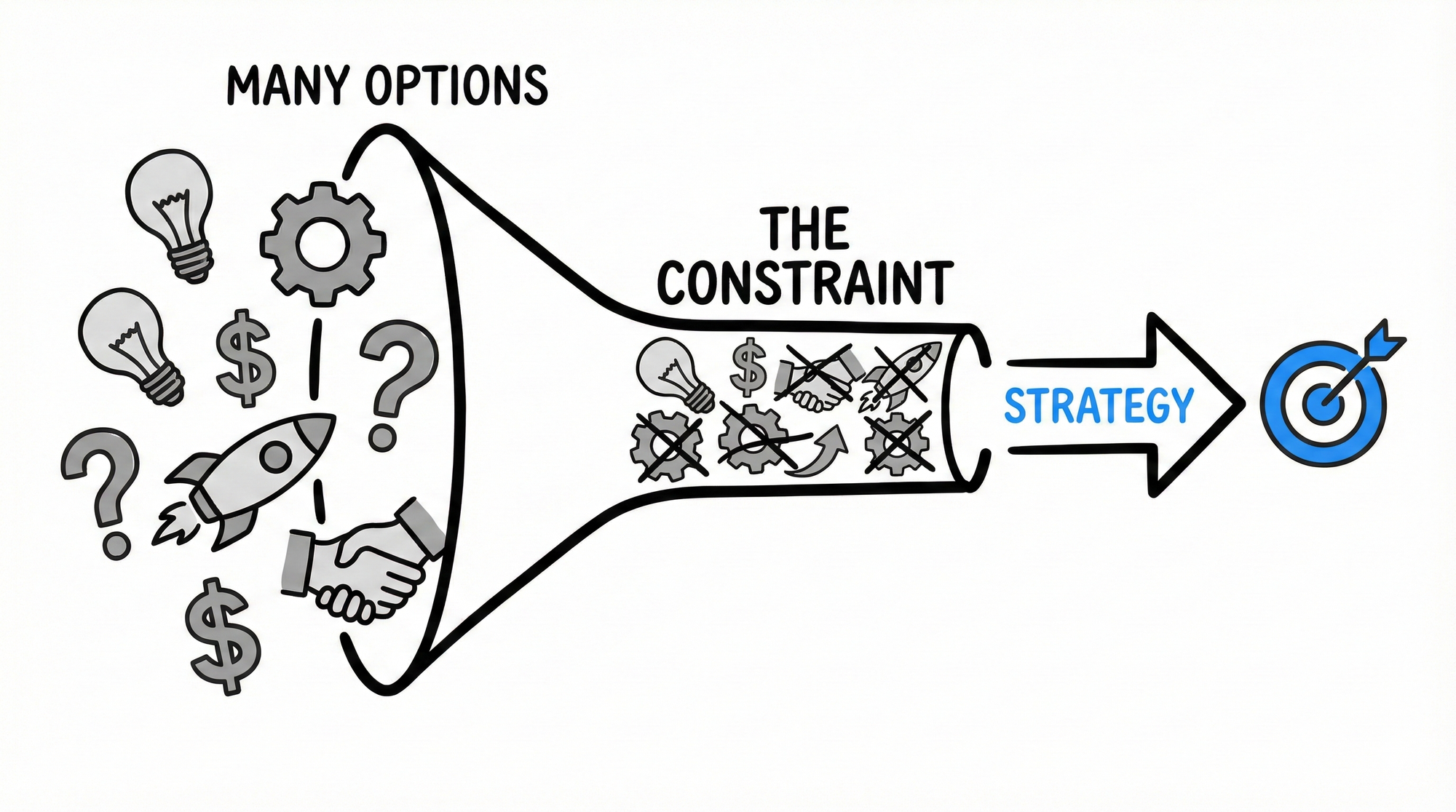

Abundance is supposed to be good. More resources mean more options. More options mean better decisions.

But that's not how it works.

When you can fund everything, you never have to choose. When there's time for every meeting, priorities remain theoretical. When every goal can be pursued, values don't get tested.

Scarcity forces choice. Choice reveals values.

Abundance hides them.

In 2008, Microsoft offered to buy Yahoo for $44.6 billion.

Yahoo's board rejected it. The price was too low, they said. Yahoo was worth more.

They had options. Plenty of cash. Time to figure it out. They could build their way back to dominance.

Except they couldn't.

With abundant resources, Yahoo never had to choose between search, content, advertising technology, and social. They pursued everything. They became good at nothing.

By 2016, Verizon bought Yahoo for $4.48 billion. One-tenth the Microsoft offer.

The abundance that gave Yahoo options prevented them from making the hard choices that would have saved them.

Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson built Basecamp with a different philosophy.

No venture capital. No unlimited runway. Bootstrapped from consulting revenue.

Every feature had to justify itself. Every hire had to pay for itself. Every product decision faced a simple test: Does this make money?

The constraint forced clarity.

They couldn't build everything, so they built one thing well. They couldn't hire everyone, so they hired carefully. They couldn't chase every market, so they picked one and dominated it.

Today, Basecamp generates tens of millions in annual revenue with a team of 60. No board. No investors. Complete control.

The constraint wasn't a limitation. It was a filter.

Jim Collins, studying companies that went from good to great, found a pattern.

The great companies had what he called a "Stop Doing List." Not just priorities. Anti-priorities. Things they explicitly chose not to do.

"Anything that doesn't fit, we don't do."

But here's what Collins noticed: companies only developed this discipline when they had to. When resources were constrained. When saying yes to everything meant failing at everything.

Abundant companies kept saying yes. They funded marginal projects. They pursued tangential opportunities. They never developed the muscle of saying no.

The constraint wasn't holding them back. The abundance was.

Chris McChesney calls it the Whirlwind. The urgent daily demands that consume attention and energy. The inbox that never empties. The meetings that multiply.

What survives the whirlwind is what actually matters. Everything else was aspiration.

But when resources are abundant, nothing has to survive. You can fund the whirlwind and the strategy. You can hire for both. You can pursue everything.

Until you can't.

And by then, you've lost the ability to tell the difference between what matters and what doesn't.

The diagnostic is simple.

If you can't name what you're NOT doing, you don't have a strategy. You have a wish list.

If every project gets funded, you're not making choices. You're avoiding them.

If no one ever says "we can't afford that," you're not learning what you actually value.

Constraints don't distort truth. They reveal it.

Abundance obscures it.

When evaluating your strategy, ask:

What are you explicitly NOT doing?

If the answer is "nothing" or "we'll figure it out later," you don't have a strategy. You have abundance masquerading as optionality.

The companies that win aren't the ones with the most resources.

They're the ones who know what to do with scarcity.

This post explores THE SQUEEZE, one of four forces from Execution Reveals. Scarcity forces choice. Choice reveals values. Abundance hides both.