The Momentum Engine

Why organizations slow down, and the physics of building faster systems

The Company That Hired 14,000 People and Fired All Its Managers

Imagine building an organization with 14,700 employees. And only 50 administrative staff.

That's Buurtzorg. A Dutch healthcare company delivering home nursing care. By every metric that matters, it shouldn't work.

8% overhead. Industry average: 25%. Fewer hours per patient. Better outcomes. Highest patient satisfaction in the Netherlands. Patients regaining independence faster. Fewer emergency hospital admissions.

The company was founded in 2006 by Jos de Blok, a nurse who'd spent years watching Dutch healthcare "optimize" itself into dysfunction. Mergers. Economies of scale. Productivity tracking. Documentation. The system became efficient at measuring itself. And patients suffered.

De Blok's solution sounded insane: nurses would form self-managing teams of 10-12 people. No managers. No middle layers. Just nurses, caring for their neighborhood.

When asked to explain Buurtzorg's success, de Blok gives a simple answer: "We don't need managers because nurses can form self-managing teams."

But that answer hides something deeper.

Buurtzorg didn't succeed because nurses are special. It succeeded because de Blok (whether he knew it or not) had architected around a set of invisible dynamics that govern every organization.

Velocity isn't about working harder. It's governed by physics.

The Invisible Physics

Every growing organization hits the same wall.

The startup that shipped daily now takes months. The team that moved in sync now schedules meetings to discuss meetings. The company that disrupted an industry now feels disrupted by its own complexity.

Leaders blame culture. Consultants blame process. Everyone agrees something broke. Nobody can name what.

What broke is physics.

I've spent years studying why organizations slow down, synthesizing patterns from 18 foundational books spanning 50 years, from Brooks's The Mythical Man-Month (1975) to Forsgren's Accelerate (2018). What emerged wasn't a management framework. It was a set of fundamental dynamics that govern organizational velocity the way physics governs falling objects.

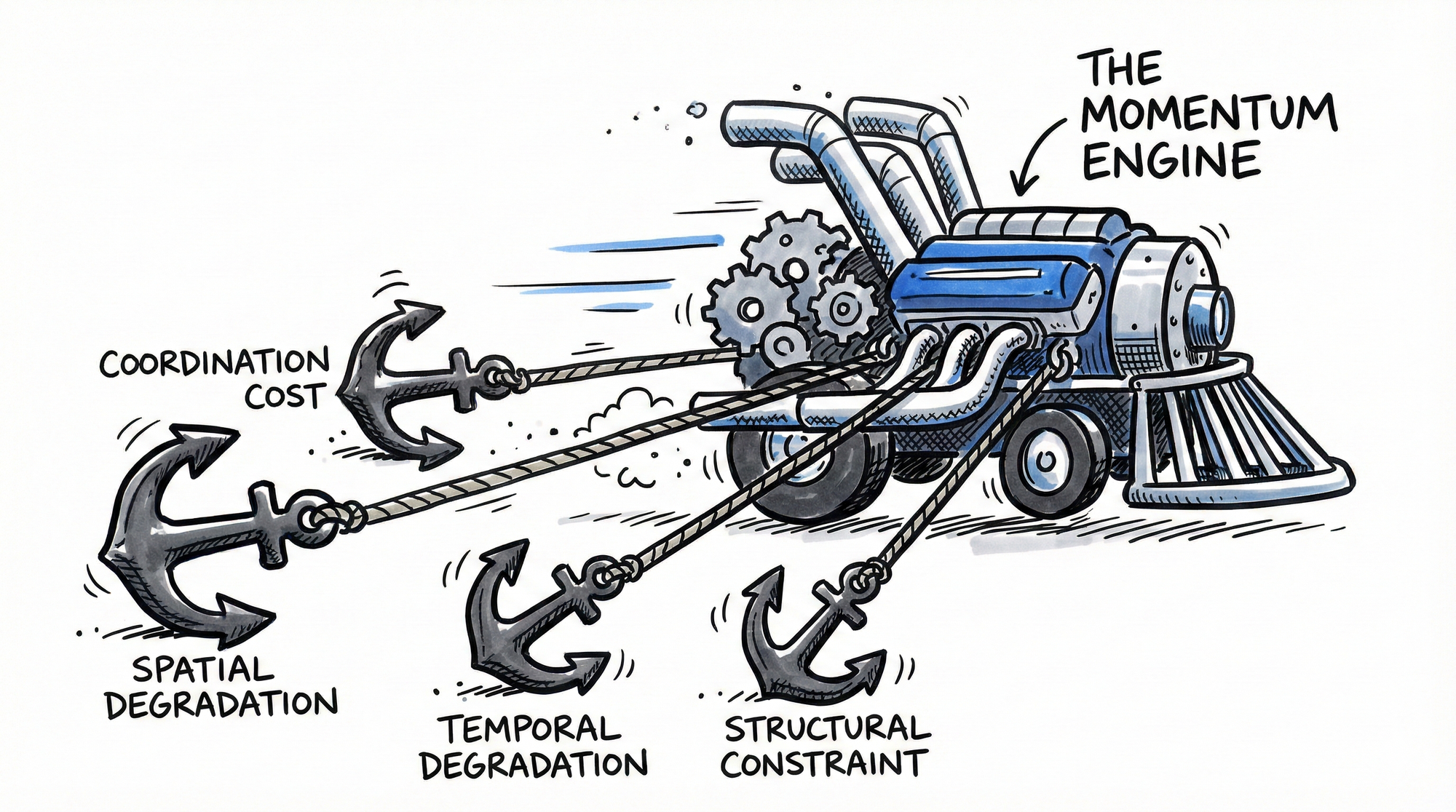

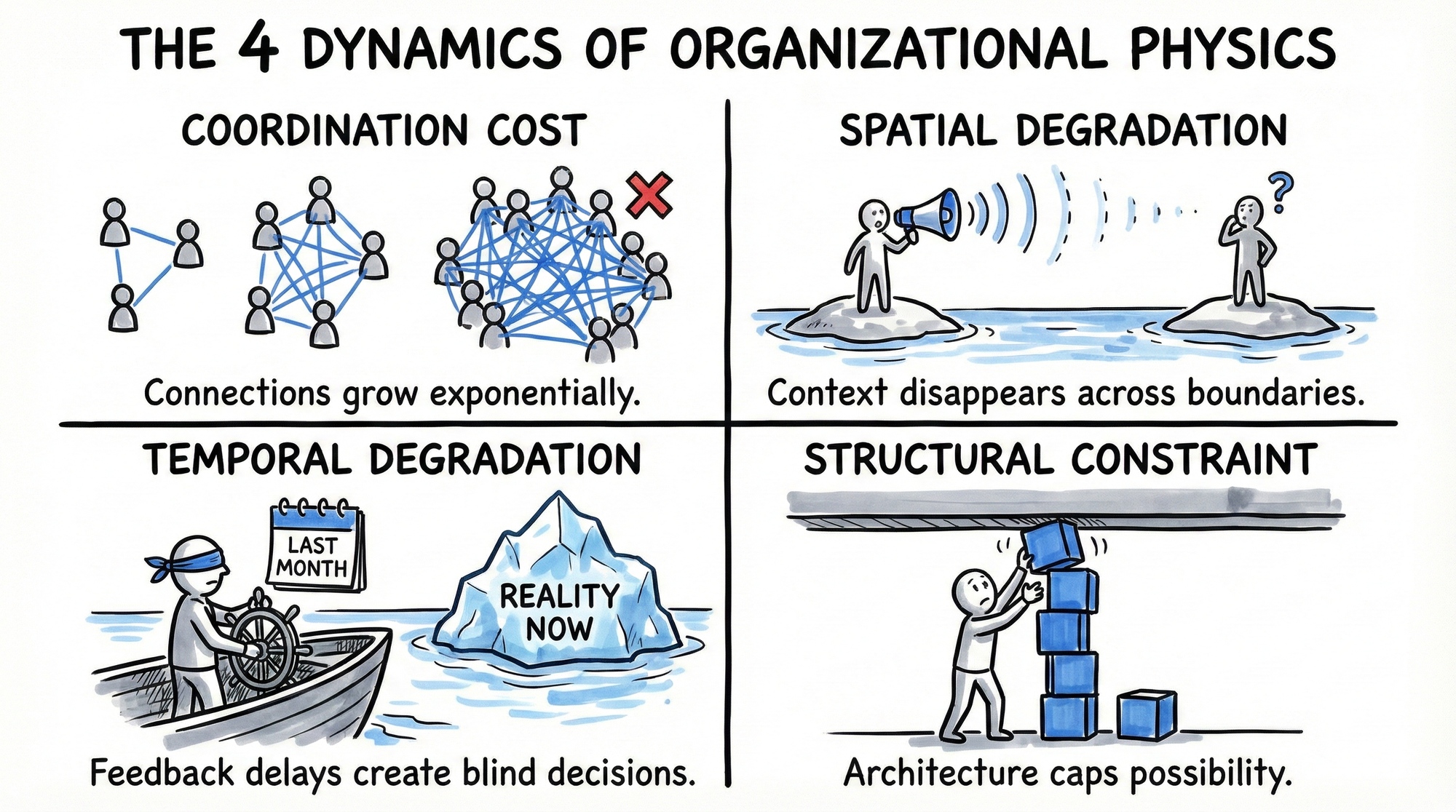

Four dynamics determine how fast any organization can move:

- Coordination Cost Scaling: Communication grows exponentially. Capacity grows linearly.

- Spatial Information Degradation: Context erodes across boundaries.

- Temporal Information Degradation: Feedback delays create blind decisions.

- Structural Constraint: Architecture caps velocity regardless of effort.

These aren't challenges to overcome. They're physics. You can't eliminate them. You can only architect around them.

Buurtzorg's team limit of 10-12? Architecting around coordination cost. End-to-end ownership? Minimizing spatial degradation. Immediate patient feedback? Collapsing temporal loops. Flat structure? Removing structural constraints.

The pattern repeats everywhere you look.

Dynamic 1: Coordination Cost Scaling

Start with something simple: moving a couch.

One person. Slow, but zero coordination needed.

Two people. Faster. One communication pathway: "On three..."

Four people. Could be 4x faster. But 6 communication pathways. Each person tracking three others.

Eight people. 28 pathways. You've invented middle management because coordination math made it necessary.

This is Brooks's Law from 1975: "Adding people to a late project makes it later."

Brooks learned it the hard way. As project manager for IBM's OS/360, he watched his team balloon from a handful of programmers to hundreds. Velocity collapsed. Every new hire made the system slower. The math was inescapable: coordination cost grows as n(n-1)/2.

| Team Size | Communication Pathways |

|---|---|

| 5 people | 10 |

| 10 people | 45 |

| 50 people | 1,225 |

| 500 people | 124,750 |

This isn't bad communication. This is combinatorial explosion.

In 1943, the U.S. Army needed a jet fighter. The Germans had superior jets. America was years behind.

Lockheed engineer Clarence "Kelly" Johnson made a proposal that seemed suicidal: give him a small team, isolate them from the rest of the company, and get out of their way.

143 days later, the XP-80 Shooting Star was built. Seven days faster than the impossible deadline.

Johnson's approach became the legendary Skunk Works. His core principle: "Restrict the number of people involved." Use 10-25% of normal personnel.

150 engineers in 18 months. Or a large team in 5 years. Same output. Different physics.

Robin Dunbar, a British anthropologist, found the brain can only maintain stable relationships with roughly 150 people. Beyond that, we simply can't track the connections. The Hutterites split communities at 150 members. Gore-Tex caps factories at 150. The constraint is biological, not organizational.

Beyond a certain team size, you have three choices: split into smaller teams, reduce required connections, or accept slower velocity.

The inversion: Adding people makes you slower. Organizations keep learning this the hard way.

Dynamic 2: Spatial Information Degradation

Emperor Augustus had a problem.

The Roman Empire stretched from Britain to Syria. 5,000 miles across. A message took 5 weeks to reach Britain. 7 weeks to reach Syria. How do you coordinate an empire when communication takes longer than conditions last?

Augustus inherited the Persian system of relay messengers: fresh riders at each station, passing messages down the line. Fast. But lossy. By the time a message reached the frontier, context was degraded. Details lost. Nuance evaporated.

So Augustus made a counterintuitive choice. Instead of relay riders, he used single couriers who traveled the entire distance.

Slower. But: "A courier who travels the whole distance could be interrogated upon arrival."

The courier carries full context. Can answer questions. Explain nuance. Fill gaps.

Even with this optimization, the empire fragmented. Emperor Diocletian split it into four parts in 293 CE. The stated reason: "too large and too complex for power to rest in the hands of one man."

Information degrades across boundaries.

Different teams have different contexts. Handoffs require compression. Compression loses nuance. Nuance contains critical information. Decisions made with degraded information fail.

Pixar learned this with their Braintrust. When it started, five people: Lasseter, Stanton, Docter, Unkrich, Ranft. Complete context. Instant communication.

As Pixar grew, they evolved two rules that preserved context despite scale:

- No authority. Directors receive feedback but retain creative control.

- Candor required. Full context must be shared, not compressed.

When Disney acquired Pixar in 2006, they tried to copy the Braintrust. For years, it didn't work. The structure was there. The trust wasn't. Context degraded because people filtered what they said.

The constraint: You cannot transfer full context across boundaries. Compression is inevitable. This is why product teams outperform component teams. It's why Augustus sent interrogatable couriers instead of relay messages.

Dynamic 3: Temporal Information Degradation

In 1959, Milton Friedman told Congress something that still haunts central bankers:

"Monetary policies operate with a long lag and with a lag that varies widely from time to time."

Friedman had studied decades of Federal Reserve policy. His finding was devastating: changes in interest rates take between 4 and 29 months to affect the economy. You can't predict where in that range any particular change will fall.

The Fed is perpetually flying blind. Decision today. Data from last month. Effect visible in 4 months to 2.5 years. By then, conditions have changed. They're always behind.

Friedman's conclusion: controlling economic activity using active monetary policy was "essentially unachievable." Fed Chair Jerome Powell still quotes this.

Now imagine this at organizational scale.

You're making decisions based on last quarter's information. By the time you see results, the world has moved. You're always responding to yesterday's reality.

This is why Forsgren's Accelerate research found such stark differences: elite performers ship multiple times per day with less than an hour from commit to production. Low performers ship monthly with lead times measured in months.

Elite performers change → see impact → adjust → repeat. In minutes. Low performers change → wait weeks → forget context → guess → wait again.

This isn't a performance gap. It's a physics gap.

Toyota understood this in 1950. The Andon cord. Any worker could stop the entire production line if they saw a defect.

Short-term: productivity plummeted. Within seven years: "Their process was nearly flawless and they were producing the best cars in the world."

Every cord pull made Toyota a little better. Feedback instant. Learning continuous.

Here's the twist most people miss:

When American car companies copied the Andon cord, they installed it. Workers were given authority to pull it.

Nobody pulled it.

Not because there were no defects. Because workers were too afraid.

The tool was there. The empowerment was not. The architecture of instant feedback requires the culture to support it.

The inversion: Speed creates quality. Not the other way around. Fast loops catch errors when they're cheap to fix. Slow loops let errors compound.

Dynamic 4: Structural Constraint

In the 12th century, architects had a problem.

Churches needed to reach toward heaven: tall, soaring, light-filled. But stone is heavy. The taller you build, the thicker your walls must be. Thick walls mean small windows. Small windows mean dark interiors.

The physics seemed immutable. Height required mass. Mass blocked light. God's house was forever dim.

Then someone invented the flying buttress.

Simple innovation: transfer lateral thrust outside the building, to separate piers connected by arched supports. The wall no longer needed to bear full load.

Notre-Dame's nave rises 115 feet. Walls thin enough for massive stained glass. The Gothic style transformed European architecture for 400 years.

Same materials. Different structure. Radically different possibilities.

The flying buttress didn't just allow taller buildings. It changed what "church" could mean. Light flooded spaces that had been dark for centuries. Architecture created possibilities that didn't exist before.

This is structural constraint.

You can have the best developers, clearest strategy, infinite budget. If your architecture won't support velocity, you're capped. Structure determines what's possible.

Conway's Law: "Organizations design systems that mirror their communication structure." You cannot build microservices with a monolithic org structure. You cannot build a monolith with loosely-coupled teams.

The Beatles. Four people. Peak of creative success. The structure that enabled their early collaboration (Brian Epstein managing, shared experiences, complementary skills) couldn't support their individual growth.

George Harrison quit briefly. John Lennon privately left September 20, 1969. Even at n=4, the structure couldn't contain what they were becoming.

The inversion: Constraints enable speed. The right structure focuses energy. The wrong structure blocks progress. Removing all constraints diffuses energy into entropy.

When the Dynamics Collide

The four dynamics don't operate in isolation. They amplify each other.

Consider a growing startup that just raised Series B.

They hire 50 new engineers. Coordination cost explodes.

They create specialized teams: frontend, backend, data, infrastructure. Each with their own context. Spatial degradation at every handoff.

Their deployment process, built for 10 people, now takes two weeks. Temporal degradation makes every cycle blind.

Their monolithic codebase can't support parallel work. Everyone waits on everyone. Structural constraint caps velocity regardless of headcount.

The cruel irony: Each solution makes other dynamics worse.

More people to go faster → more coordination cost. More process to manage complexity → slower feedback. More specialization for efficiency → more handoffs, more context loss.

This is why "scaling" feels impossible. You're not solving one problem. You're navigating four interacting dynamics that amplify each other's constraints.

But What About Amazon?

You might be thinking: If these dynamics are physics, how do Amazon, Google, and Netflix scale to tens of thousands of engineers?

They don't escape the physics. They architect around it.

Amazon's two-pizza teams aren't management philosophy. They're coordination cost engineering. Each team small enough that n² doesn't explode. APIs between teams replace coordination meetings.

Netflix's continuous deployment isn't speed for its own sake. It's temporal architecture. Thousands of deployments per day. Feedback loops in minutes.

Spotify's squads, tribes, and guilds aren't org chart innovation. They're structural engineering. Loosely coupled teams minimize coordination. Guilds prevent context silos.

These companies didn't transcend the physics. They designed around it so thoroughly that the constraints become invisible.

The Diagnostic

How do you know which dynamic is killing you?

"We were faster when we were smaller." Coordination cost scaling. Smaller teams. Clearer boundaries. Explicit interfaces.

"It got lost in translation." Spatial degradation. Fewer handoffs. Ubiquitous language. End-to-end ownership.

"We don't know what's happening." Temporal degradation. Faster deployment. Better instrumentation. Smaller batches.

"The system won't let us." Structural constraint. Architectural refactoring. Seams for change. Team restructuring.

Most organizations experience all four simultaneously. Start with the one that hurts most. Small wins create momentum for bigger changes.

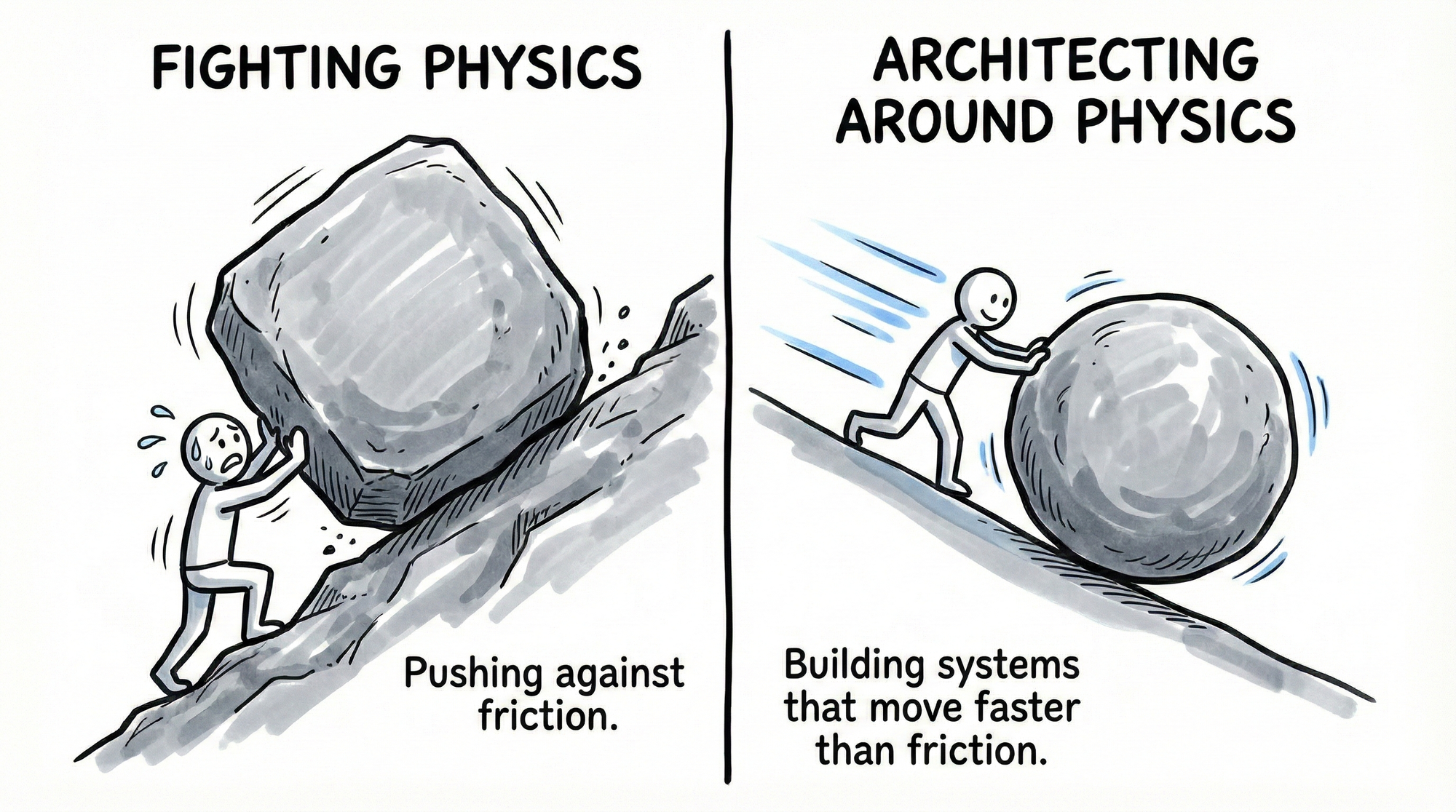

Architecting Around Physics

The fastest companies aren't moving faster. They have less friction.

Buurtzorg succeeded because Jos de Blok architected around all four dynamics:

- Teams of 10-12. Below coordination cost explosion.

- End-to-end ownership. No handoffs, no context loss.

- Immediate patient feedback. Temporal loops collapsed.

- Simple structure. No hierarchy blocking change.

The principles are universal:

- Minimize coordination requirements. Small teams. Clear boundaries. Explicit interfaces.

- Preserve context across boundaries. Ubiquitous language. End-to-end ownership. Minimize handoffs.

- Collapse feedback loops. Continuous deployment. Automated testing. Observability.

- Design evolvable architecture. Modularity. Seams for change. Bounded contexts.

The Close

Every organization that grows will hit these physics. The question isn't whether you'll encounter them. You will. The question is whether you'll recognize them when you do.

Most organizations respond to slowing velocity by working harder. More people. More process. More documentation. More meetings.

These responses make things worse. They fight the physics instead of architecting around them.

Jos de Blok built Buurtzorg on one principle: "Humanity over bureaucracy."

But the real insight was deeper: Structure over effort.

You can't outwork physics. You can't outprocess physics.

You can only build systems that move faster than friction.

The Momentum Engine isn't about velocity.

It's about architecture.

Build accordingly.

Explore Further

Each of the four dynamics has its own deep dive:

The Dunbar Trap — The biological ceiling on team size that nobody talks about. Explores COORDINATION COST SCALING.

Why Handoffs Kill — The hidden cost every time work changes hands. Explores SPATIAL INFORMATION DEGRADATION.

The Andon Paradox — Why copying Toyota's tools fails without copying Toyota's culture. Explores TEMPORAL INFORMATION DEGRADATION.

Conway's Law in Practice — Your org chart is your architecture, whether you like it or not. Explores STRUCTURAL CONSTRAINT.

The Series B Death Spiral — How the four dynamics compound into organizational collapse.